Top Essay Writers

Our top essay writers are handpicked for their degree qualification, talent and freelance know-how. Each one brings deep expertise in their chosen subjects and a solid track record in academic writing.

Simply fill out the order form with your paper’s instructions in a few easy steps. This quick process ensures you’ll be matched with an expert writer who

Can meet your papers' specific grading rubric needs. Find the best write my essay assistance for your assignments- Affordable, plagiarism-free, and on time!

Posted: August 29th, 2022

An Investigation into Off-Site Manufacturing and the Barriers it Faces in the UK Housing Industry

We get a lot of “Can you do MLA or APA?”—and yes, we can! Our writers ace every style—APA, MLA, Turabian, you name it. Tell us your preference, and we’ll format it flawlessly.

Table of Contents

Totally! They’re a legit resource for sample papers to guide your work. Use them to learn structure, boost skills, and ace your grades—ethical and within the rules.

Starts at $10/page for undergrad, up to $21 for pro-level. Deadlines (3 hours to 14 days) and add-ons like VIP support adjust the cost. Discounts kick in at $500+—save more with big orders!

100%! We encrypt everything—your details stay secret. Papers are custom, original, and yours alone, so no one will ever know you used us.

2.1 Introduction to the Chapter

Nope—all human, all the time. Our writers are pros with real degrees, crafting unique papers with expertise AI can’t replicate, checked for originality.

2.2.2 History of Off Site Production

2.2.3 Current use of Off Site Production

Our writers are degree-holding pros who tackle any topic with skill. We ensure quality with top tools and offer revisions—perfect papers, even under pressure.

2.3 Current Methods of Off Site Production

Experts with degrees—many rocking Master’s or higher—who’ve crushed our rigorous tests in their fields and academic writing. They’re student-savvy pros, ready to nail your essay with precision, blending teamwork with you to match your vision perfectly. Whether it’s a tricky topic or a tight deadline, they’ve got the skills to make it shine.

2.3.4 Sub-Assemblies and Components

2.3.5 Future Modern Methods of Construction

2.4 Advantages of Off Site Production

Guaranteed—100%! We write every piece from scratch—no AI, no copying—just fresh, well-researched work with proper citations, crafted by real experts. You can grab a plagiarism report to see it’s 95%+ original, giving you total peace of mind it’s one-of-a-kind and ready to impress.

Yep—APA, Chicago, Harvard, MLA, Turabian, you name it! Our writers customize every detail to fit your assignment’s needs, ensuring it meets academic standards down to the last footnote or bibliography entry. They’re pros at making your paper look sharp and compliant, no matter the style guide.

2.5 Disadvantages Associated with Off Site Production

2.5.1 Higher Upfront Capital Costs

2.5.3 Transportation Difficulties

For sure—you’re not locked in! Chat with your writer anytime through our handy system to update instructions, tweak the focus, or toss in new specifics, and they’ll adjust on the fly, even if they’re mid-draft. It’s all about keeping your paper exactly how you want it, hassle-free.

2.7 Barriers OSM faces in the UK Housing Industry

It’s a breeze—submit your order online with a few clicks, then track progress with drafts as your writer brings it to life. Once it’s ready, download it from your account, review it, and release payment only when you’re totally satisfied—easy, affordable help whenever you need it. Plus, you can reach out to support 24/7 if you’ve got questions along the way!

3.2 Issues Arising from the Literature Review

Need it fast? We can whip up a top-quality paper in 24 hours—fully researched and polished, no corners cut. Just pick your deadline when you order, and we’ll hustle to make it happen, even for those nail-biting, last-minute turnarounds you didn’t see coming.

Absolutely—bring it on! Our writers, many with advanced degrees like Master’s or PhDs, thrive on challenges and dive deep into any subject, from obscure history to cutting-edge science. They’ll craft a standout paper with thorough research and clear writing, tailored to wow your professor.

3.7.1 Limitations to Case Study

We follow your rubric to a T—structure, evidence, tone. Editors refine it, ensuring it’s polished and ready to impress your prof.

3.8 Approaches to Data Analysis

Send us your draft and goals—our editors enhance clarity, fix errors, and keep your style. You’ll get a pro-level paper fast.

4.2.1 Advantages and Disadvantages of OSM

4.2.2 Barriers Restricting the use of OSM in the UK

4.2.3 Requirements to Promote the use of OSM

4.2.4 Innovation & Future in the Housing Industry

Yep! We’ll suggest ideas tailored to your field—engaging and manageable. Pick one, and we’ll build it into a killer paper.

5.3 Improvements and Further Research

Yes! Need a quick fix? Our editors can polish your paper in hours—perfect for tight deadlines and top grades.

Sure! We’ll sketch an outline for your approval first, ensuring the paper’s direction is spot-on before we write.

Index of Figures and Tables

Figure 1 – Dissertation Design

Figure 2 – New build, share by construction type in the UK (2008 to 2015)

Figure 3 – Percentage used and considered in the last 3 years.

Figure 4 – Percentage of MMC used on-site

Figure 5 – 3D Printed villa built by WinSun

Definitely! Our writers can include data analysis or visuals—charts, graphs—making your paper sharp and evidence-rich.

Figure 6 – On-site Construction Time

Table 1 – Different construction method requirements

Table 1 – On-site Construction Time

List of Abbreviations

BIM – Building Information Modeling

CNBN – State Owned Chinese Construction Company

CNC – Computer Numerical Control

EFM – Emergency Factory Made

HSE – Health and Safety Executive

MMC – Modern Methods of Construction

We’ve got it—each section delivered on time, cohesive and high-quality. We’ll manage the whole journey for you.

NHBC – National House Building Council

OSM – Off-Site Manufacturing

RFI – Radio Frequency Identification

Abstract

Despite the economic challenges the UK housing industry has recently faced, construction continues to be one of the most profitable economic sectors in the UK, contributes over £103 billion to the UK economy and comprises over 280,000 businesses (Chris Rhodes, 2015). With the growing demand for new developments and affordable housing, it would be expected that housing developers would strive to be the leaders in research and development to reduce building time and costs. However, the Government Department of Business, Innovation and Skills has indicated that the construction contracting industry lacks innovation, relative to other industries.

Yes! UK, US, or Aussie standards—we’ll tailor your paper to fit your school’s norms perfectly.

Ever since the Egan report ‘Rethinking Construction’ was published in 1998, the government has considered Off-Site Manufacturing (OSM) a suitable replacement for traditional construction methods. Since then, the construction industry has seen a substantial growth in OSM and Modern Methods of Construction (MMC). Shahzad et al. (2015) further elaborates that OSM and MMC expedite the construction process by up to 50 per cent and is a more cost effective method in the design and planning stages.

OSM is a construction method that is defined by Pan et al. (2008) as a means ‘where buildings, structures or parts are manufactured or pre-assembled prior to their installation on-site.’ However, they also stated that in recent years, the construction industry has been branded as inefficient and has been exhorted to increase its utilisation of offsite technologies or MMC in order to address the under-supply and poor quality of housing. In other large industries, innovation and development are essential business strategies for firms’ survival and growth.

According to Pan et al. (2008) there is already a choice of global manufacturers developing OSM. However, despite the proven benefits of such technologies, the take-up of OSM within the UK housing industry has been slow. Figures from the National House Building Council (NHBC) representing over 80 percent of new developments in the UK, report in 2016 that 70% of housing developments still utilise traditional building methods. The remaining 30% are made up by light gauge steel frame, timber frame and other MMC. This figure has been fairly consistent over the past 8 years.

The history of innovation in OSM in the UK is protracted. In the post-war period there was a housing crisis with an estimated need of 200,000 homes to be developed quickly. In 1949, the proposed solution was an ‘Emergency Factory Made’ (EFM) program, which eventually delivered 153,000 ‘temporary’ prefabricated homes. Alongside these homes were ‘permanent’ non-traditional homes. Most of these 450,000 non-traditional homes were built in the decade following the war (NHBC, 2016).

In an attempt to increase OSM in the housing sector, several reports were published, such as the Latham report, ‘Constructing the Team’ in 1994 and the Egan report ‘Rethinking Construction’ in 1998. These reports utilised experiences from other industries, such as industrial manufacturing, to identify ways to increase efficiency and reduce waste. Although we currently see an industry that has continued to use masonry cavity wall construction for low-rise residential new developments, the success of OSM homes seen in other parts of the world, such as Scandinavia and Japan, has not generally been replicated in volume in the UK.

If your assignment needs a writer with some niche know-how, we call it complex. For these, we tap into our pool of narrow-field specialists, who charge a bit more than our standard writers. That means we might add up to 20% to your original order price. Subjects like finance, architecture, engineering, IT, chemistry, physics, and a few others fall into this bucket—you’ll see a little note about it under the discipline field when you’re filling out the form. If you pick “Other” as your discipline, our support team will take a look too. If they think it’s tricky, that same 20% bump might apply. We’ll keep you in the loop either way!

During the post-war period, quality was overlooked, and over time it became impossible to obtain a mortgage for many of these prefabricated homes due to structural instability and poor build quality. As a result, this tarnished the image of OSM, and deemed it as poor value and substandard in comparison to homes built using traditional methods (NHBC, 2016).

Despite the tarnished image of OSM in the UK, it has proven its capabilities in other countries and specialist developers are nowadays able to produce large, bespoke, luxury homes that can be delivered on trailers at a lower cost and in a shorter time frame. There are several foreign developers from Scandinavia and Germany that offer bespoke pre-fabricated homes in the UK and foreign investments that are now coming into the UK housing industry indicate that the UK’s outdated views on MMC and OSM could be the main barriers that hinder OSM to reach its full potential.

The aim of this dissertation is to investigate and explore Off-Site Manufacturing (OSM) as a Modern Method of Construction and the barriers OSM faces within the UK Housing Industry.

The objectives are to:

Our writers come from all corners of the globe, and we’re picky about who we bring on board. They’ve passed tough tests in English and their subject areas, and we’ve checked their IDs to confirm they’ve got a master’s or PhD. Plus, we run training sessions on formatting and academic writing to keep their skills sharp. You’ll get to chat with your writer through a handy messenger on your personal order page. We’ll shoot you an email when new messages pop up, but it’s a good idea to swing by your page now and then so you don’t miss anything important from them.

I. Critically appraise the advantages and disadvantages of OSM in the construction industry.

II. Investigate the current use of OSM techniques and gain an insight from industry professionals to explore the reasons behind the slow adoption of OSM and the barriers it currently faces.

III. Examine what factors are required for OSM to become a leading building technique and investigate its possible future development.

IV. Investigate whether there is a lack of innovation within the UK’s construction housing industry and explore the reasons behind this.

Step 1 – Literature Review

Step 2 – Develop Semi Structured Interview

Step 3 – Conduct Interviews

Step 4 – Analysis of Interviews

Step 5 – Conclude Data

Step 6 – Recommend Further Research

Figure 1: Dissertation Design

This chapter uses current industry literature surrounding OSM, MMC and traditional methods within the UK housing industry. The literature was obtained through multiple secondary sources and includes those written by experienced authors such as Taylor, Gibb, Fawcett and a list of comprehensive reports provided by the NHBC and HSE. It provides an in-depth analysis on the current and historical use of these methods, alongside the current perception of OSM in the housing sector in addition to the advantages and disadvantages associated with these methods of construction.

This chapter identifies which research method was most appropriate for the collection of data. For the purpose of this analysis, qualitative data collection methods was used consisting of semi structured interviews and a case study with information about the interviewee’s job and sector. The approach for the data analysis has been provided in addition to any limitations that affect the collection of data.

This chapter is used to analyse the primary data that was collected. A coding process was utilised to find common and re-occurring themes in the interviews allowing for comparisons to be made. The analysed data was also subjected to a process of triangulation against the literature.

This chapter summarises and compares the key points found in the literature review and interviews in relation to the research objectives. It also identifies possible limitations and constraints faced by the research question along with recommendations of further reading.

This chapter explores the current views regarding OSM, MMC and traditional methods used in the UK housing industry using a selection of secondary data sources available in the public domain. A brief overview of the history surrounding OSM is discussed to give the reader a greater understanding of the topic.

In addition to the definition of OSM provided by Pan et al. (2008), Windle (2004:2) noted the difficulty in defining ‘modern’ methods of construction, stating that the terminology “perplexed many in the house building industry.” Kempton, (2009) explained that this is due to the number of distinct terms and acronyms that are also used, such as ‘modular construction,’ ‘off-site production,’ ‘prefabrication’ and ‘non-traditional.’ Kempton, (2009) described MMC as a generic term consisting of a range of construction techniques. Within the UK, traditional methods for housing are defined by Windle (2004:2) as ‘building with brick and block walls and a timber supported pitched, tiled or slated roof.’

A report by Taylor, (2009) published by the HSE, stated that the end of World War I could be considered the origin of OSM due to the combination of a major shortage of a skilled workers and a lack of building materials which resulted in a severe shortage of housing and prompted the search for a solution. Between the wars from 1918 to 1939, 4.5 million houses were developed. However, only 5% of these houses were built using new methods of construction. A method of pre-fabrication was tested in Dudley during this time. 600 cast iron panels which were bolted together and lined with asbestos to form the structure of the building but only 4 houses were developed using this technique due to high costs and poor thermal insulation (BCLM, 2003).

The end of World War II prompted another increase in housing demands. Taylor, (2009) explained that in addition to replacing houses destroyed during the war, the government in 1945 published a white paper. The emphasis of this paper was that the government wished to supplement traditional building operations with methods of construction that capitalised on the surplus of steel and aluminum production from industries geared to war output. These factories required diversification to survive the change after the war, driving the industry towards prefabrication and resulted in many varieties of concrete, timber, steel and hybrid framed systems

During the 1950s and 1960s, the UK Construction Industry moved towards an industrialised form of building and the benefits of OSM in the housing industry were tested on a larger scale. Those in favour of OSM promoted industrialised building methods with an ever growing confidence but those who lived in the newly developed homes using OSM, remained suspicious about MMC. A critical turning point for OSM was the collapse of Ronan Point in 1968, coupled with numerous other problems associated with large panel high-rise buildings. Ronan Point was a high rise apartment block built from pre-fabricated concrete panels, a technique developed to help solve the housing crisis. Verlaan (2011) gave details of the disaster stating that the reduced time and costs of the development led to a lack of quality control. Although it was found that poor workmanship during the construction stage caused the collapse, the public blamed the architects’ modernist planning principles for the failure. The author went on to explain that Ronan Point was quickly re-built in order to reassure the public about the safety of MMC. However, the damage was already done. Soon after the collapse, social problems combined with continued bad press about construction faults caused the downfall of MMC in Great Britain.

Taylor, (2009) stated that during the 1980s, the majority of prefabricated homes were dominated by timber framed dwellings which grew to about 30% of new builds. However, the industry suffered a major downturn when several fires, caused by arson, broke out in these houses which gained them a lot of bad publicity. This, combined with coverage in the 1980s TV program ‘World in Action’ reporting on a case study of a small number of poorly developed houses in the West of England convinced viewers that timber framed houses were rotting and not watertight. Although the report was later disproved, Taylor, (2009) stated that this notion is still quoted today as a justification for choosing traditional forms of construction.

To this day, assumptions are still made by a large proportion of construction industry professionals and those who procure construction projects that off-site solutions have failed in the past and that off-site production is more expensive than traditional on-site methods of construction (Taylor, 2009). Statistics provided by the NHBC, (2016) emphasised this statement with figures showing that only approximately 30% of newly developed homes in the past 8 years have been constructed using MMC.

The UK market for OSM has improved over the last couple of years, underpinned by recovery and growth in the general economy. A report written by Hartley and Moore, (2016) stated that between 2008 and 2013, OSM market values declined due to the economic recession. However, the recent demand for housing developments has never been greater. Leech, (2017) reported that the current UK housing demand requires approximately a quarter of a million new homes, whilst the current output is only around 170,000. The shortage is linked to many factors surrounding the industry, some triggered by the recent recession resulting in a shortage of skilled workers and materials, as well as a pressure to reduce waste and improve efficiency. With an increasing demand for housing developments and the evident concern over another economic downturn, companies are now looking into more cost effective, sustainable, and efficient construction methods.

Other countries have had more success in implementing OSM. Sweet, (2015) stated that Sweden and Japan are producing as much as 85% of their homes using OSM. This success may be attributed to Sweden’s freezing winters and environmental activism whilst Japan might be driven by high population density and the threat of earthquakes. Until recent years, there has been no drastic requirement to change the way we build homes in the UK.

One key factor that is expected to drive up demand and use for OSM is Building Information Modelling (BIM). Hartley and Moore, (2016) explained that it became mandatory for public sector construction projects to implement the use of BIM after April 2016. BIM is digital representation of the building process facilitating the exchange and interoperability of information. Key advantages are that it can streamline building design, procurement, construction and maintenance processes as well as facilitate standardisation in design which favors the use of OSM. Although BIM is yet to become an essential part of construction within the private sector, Ezcan et al. (2013) explained that BIM can be seen as one of the most apparent aspects of a deep and fundamental change that is rapidly transforming the construction industry. Used at its full potential it could be employed as a facilitator for new technologies. However, Ezcan et al. (2013) also stated that despite the proven benefits of BIM, smaller contractors and housing developers may not have the financial capability, nor the technical knowledge required to utilise BIM.

Despite the recent government push for the full implementation for BIM, Suchocki, (2017) believed that many industry professionals view BIM as another temporary fad or short term trend, similar to previous attempts to introduce new technologies into the construction industry. Although literature suggests that there has been an increase in the use of OSM, a report published by the NHBC, (2016) shown in Figure 2, indicated very little change in construction methods used in the housing industry over the past 8 years.

Figure 2: New builds by construction type in the UK 2008 -2015 (NHBC, 2016, p.9)

To gain a better understanding of the current use of OSM, financial reports from the top five housing developers offer an insight into the expenditure on research and development and their use of MMC/OSM. Simon, (2017) ranked the top five housing developers based on their output of houses in 2015. Combined they produced 54,184 homes in 2015, however, out of these homes, only approximately 7,000 (12.9%) were built using MMC. Persimmon, the UK’s second largest house builder by output, uses modular construction techniques at its ‘Space4’ factory to manufacture timber framed panels, but has stopped short of manufacturing entire homes or sections off-site. In 2015 they produced around 5,900 homes using off-site technologies, which represents 43% of their entire output (Persimmon, 2017). It needs to be assessed whether the use of OSM is a contributing factor to their higher profitability over the other four developers. Taylor Wimpey, the UK’s 3rd largest house builder by output, shut down its award-winning timber frame manufacturing business, Prestoplan, in 2014 for financial reasons (Gardiner, 2014).

In other industries, leading companies could be expected to pave the way for new technologies and innovative techniques allowing them to continue to dominate the market. However, Evans, (2016) explained that house builders have become “extremely efficient” at using traditional methods; therefore, bringing in off-site units that may not save them much time, would require large investments and a complete change of business strategy.

Prior, (2016) reported that Laing O’Rourke, the largest privately owned construction company in the UK, is currently attempting to enter the OSM market, and is expected to start working on a new £150 million pound mega factory capable of producing 10,000 new homes per year. However, they are known to have taken a huge risk on OSM being the future of the industry. Gardiner, (2016) indicated that this strategic move was instigated last year and has now caused the business to halt its investment in its new state-of-the-art off-site manufacturing facility due to internal financial issues.

In addition to Laing O’Rourke’s investment into OSM, Ogden, (2016) stated that a new business, Legal and General Homes, has signed a long-term lease with Logicor on a 550,000 sqft factory which aims to modernise the UK housing industry. It will be the largest OSM factory in the world and will apply leading edge manufacturing techniques which have already been recognised across continental Europe where off-site manufacturing of housing is increasingly common.

A report by Morby (2017) recently announced the joint venture between companies in China and UK for a £2.5 billion pound investment to create six mega factories across the UK set to deliver 25,000 new homes by 2020 in an attempt to transform the pace of delivery of new homes in the UK.

There is an emerging market for OSM at the higher end of the housing industry with many specialist European developers capitalising on OSM’s superior quality, producing bespoke panelised or modular houses that arrive on site on the back of a lorry. It is reported by Wang, (2017) that by using techniques such as Radio Frequency Identification (RFI), the houses can be erected in under a week.

Leech, (2017) announced early in the year that the government is releasing a new white paper aiming to streamline the current planning process, attract new investors and players into the industry and help increase investments for smaller developers trying to enter the OSM market as the government sets a new target of one million new homes by 2020. Slezakowski, (2017) the owner of SIG Off-Site Modular Homes, stated that in order to fully utilise OSM, there must be a collaborative effort between all parties involved, from local authorities to architects and engineers.

An indication for the need for change on a bigger scale is discussed by Burton, (2016) who indicated that the NHBC, a warranty provider for the majority of major UK developers, paid out more than £87 million to nearly 11,000 homeowners in 2015 for repairs on properties inadequately built. This figure was up 10% from 2014 and up 68% from 2006. This statistical comparison could be an indication that the increased pressure on developers to produce homes more quickly could create a similar situation to that found after the war when the public had been unaware of the poor built quality of their homes until years after their purchase.

An issue explored by Wright, (2006) revealed that just under half a million homes in the UK have had planning permission granted, but have yet to be developed. He continued to explain that the UK’s largest developers have been accused of profiting off the back of the country’s housing crisis by restricting the supply of new homes so that house prices continue to rise.

With the housing industry falling behind Brandon Lewis, the UK’s housing minister, explained that organisations were at risk of being left behind if they failed to capitalise on the advancements in new technologies such as OSM ( Apps, 2016).

As a result of the failure of ‘traditional’ construction methods to deliver a sufficient number of homes, momentum has been growing for a renewed role for OSM and MMC to help bridge the gap between demand and supply.

There are many variants of OSM with their individual and unique advantages across the construction industry. However, for the purpose of this research question, the methods of OSM that will be explored have been classified by Ross et al, (2006) as: Modular, Panellised, Hybrid, Sub-Assemblies and Components and Future MMC.

The usage of OSM/MMC over the past 3 years was explored by the NHBC, (2016). The percentage of companies using or considering to use OSM is displayed in Figure 3 showing that the majority of organisations surveyed considered themselves to be trend followers and not industry leaders, even though the majority felt that OSM/MMC will play a fundamental role in improving the efficiency of construction and overcoming the current shortages. Over half believed that the use of panelised systems will dramatically increase over the next 3 years.

Figure 3 – Percentage used and considered in the last 3 years.

Modular systems have a number of applications in the construction industry and can also be referred to as volumetric systems. Ross et al. (2006) defined this method as ‘three-dimensional units produced in a factory, fully fitted out before being transported to site and stacked onto prepared foundations to form the dwellings.’ These fully fitted-out ‘building blocks’ can be made from most materials including steel, timber, concrete and composites and are produced off-site in controllable factory conditions.

Rogan, (2000) stated that this method of construction has been around since the 1970s and is commonly seen in high rise apartments, student accommodation, budget hotels and schools due to the benefits of economies of scale. He further explained that the benefits seen from volumetric systems are a reduction in overall project time, increased quality, reduced waste, and the benefit of single point procurement. These benefits are clear when comparing the costs and value of modular construction to more traditional techniques.

Pods are another type of modular units usually used for bathrooms, kitchens or other highly serviced areas. Pods are typically non-load bearing and can be built off-site and installed when needed, allowing for simultaneous construction on-site and off-site (Rogan, 2000). Modular construction is most efficient when used for large numbers of identical units, and is slowly being used in the UK housing industry recently supported by several large, government backed investments into the modular housing factories aiming to deliver large numbers of affordable homes to help reduce the current shortage.

A report by Venables and Courtney, (2004) stated that the utilisation of modular buildings has been more widely adopted in continents such as Asia, Northern Europe and North America with the majority of developers using timber framed modules and folding roof systems.

Fawcett et al. (2005) described the panelised system as ‘units that are produced in a factory and assembled on-site to produce a three dimensional structure’.

Many have described this type of construction as ‘flat pack,’ which has tarnished the image of this construction technique, deeming it as cheap and poor quality which can often be said of other flat pack products. However, disregarding the tarnished image of the term ‘flat pack’, Fawcett et al. (2005) stated that panelised systems have had great success within the construction industry. Its use allows for greater design flexibility and reduced transport costs in comparison to modular systems. Panelised systems require greater amounts of time and labour to assemble onsite in comparison to modular systems. However, the benefits of OSM panels are still apparent and can serve as an ideal alternative to traditional methods. (Fawcett et al. 2005)

There are many different forms of panelised construction and many types of building materials can be used. According to Taylor, (2009) the main types are:

Open panels: These panels come with all components fitted and ready to be installed on site. However, all structural components are visible. These panels can be either structural or non-structural.

Advanced panels: These panels are fully finished components that slot into a pre-assembled structural frame. They can have factory fitted windows, doors, services, internal wall finishes and external cladding.

The panels are typically made from timber or light gauge steel which are then fitted with other components and finishes.

Hybrid systems use a combination of panelised and modular techniques. According to Fawcett et al. (2005) in this type of construction, modular pods are used in areas that require high levels of services and quality, such as kitchens and bathrooms. Dann, et al. (2013) stated that the pods are installed once the structural frame of the building has been erected using panels. This system allows for the greatest design flexibility and is most commonly seen in high rise student accommodation, schools and budget hotels.

According to statistics provided by the NHBC, (2016) sub-assemblies and components are most commonly used on-site, as shown in Figure 4. Among others, pre-cast chimney kits, pre-formed roof trusses, wiring looms, door frames and even foundation components are the most commonly used forms of MMC for the majority of developers in the UK as they work seamlessly alongside traditional building methods. Taylor, (2009) explained that the components arrive on-site, as and when they are needed. As a result, this can drastically reduce time, labor and site storage requirements, as workers continue working on other parts of the project whilst the components are being assembled in the factory.

Figure 4 – Percentage of MMC used on-site (NHBC, 2016, p.11)

Many industry professionals suggest big changes are imminent in the global construction industry. A common theme is the utilisation of robotic drones and 3D printing technology. Dillow, (2016) suggested that in the future drones could save the industry 10% on overall expenditure equating to around £110 million in the UK. Technologies, such as infrared 3D site mapping and automated virtual models, are already being tested by companies in the United States. Drones are capable of working quicker, more accurately and can eliminate the need for costly on-site visits. Future plans also include the collaboration with 3D printing companies to create building blocks and new composite building materials that are lifted into place by automated drones.

Star (2015) suggested that the use of 3D printing is already becoming a reality in the construction industry with the help of super-sized printers using a special designed composite mixture that is thicker and stronger than concrete. These 3D components and structures do not have the same design constraints that may hinder traditional building methods and can produce intricate designs and curved, hollowed structures that use less material and create additional space for services.

Star (2015) reported that in 2014, the Chinese company ‘Win Sun’ claimed to have built ten 3D printed houses in 24 hours. In 2015, Win Sun also had printed a 5-story apartment building and a 1,100 square meter villa, (actual build price $161,000) complete with decorative elements inside and out which is on display in China. Win Sun claimed that the 3D process can save between 30 and 60 percent of construction waste, can decrease production times by between 50 and 70 percent and can reduce labor costs by between 50 and 80 percent. It is apparent that 3D printing is an environmentally friendly and cost effective technique that also allows for complex designs.

Figure 5 – 3D Printed villa built by WinSun (Star, 2015)

The advantages of OSM are often overlooked as traditional methods are conveniently perceived as the most simplistic. Current literature typically only compares OSM against current industry practice, and the bigger picture, including the future of OSM, is often overlooked. This narrow mindset could be caused by a lack of knowledge and an unwillingness for change and will be further explored with primary data.

The development of OSM has always been linked to current housing market pressures which, the NHBC, (2016) identified as:

■ High customer demand with shortfalls in supply

■ Shortage of skilled labour and materials

■ Drive for reduced construction time

■ Goals to achieve higher quality with low energy consumption

■ Environmental impact

Leech, (2017) stated that a government white paper set to be released in 2017, will confirm these issues and set new targets for the construction industry to be achieved by 2025.

Table 1 provided by Clancy, (2016) showed a triangular model of construction requirements. Burton, (2016) stated that major UK housing developers are capable of creating new homes in record breaking time, with the government pushing to reduce that time even further, which will ultimately reduce costs for the developer. Whilst upper market, smaller developers often take much longer to develop bespoke properties. However, as shown in the Table 1 the build quality is often neglected by major developers who aim to produce high quantities and not high quality. According to Clancy, (2016) a high quality build process, when done efficiently, is always costly. The use of OSM aims to increase scope and quality whilst reducing time and costs.

Table 1 – Typical triangular model of project requirements (Clancy, 2016)

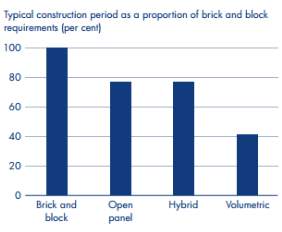

Table 2, provided by Fawcett et al. (2005) shows basic differences in the project schedule and duration of different construction methods. Although these figures do not take into consideration the cost nor the pre-construction design duration, it is evident that OSM methods require less site labour. Other trades are either not needed or can begin work for internal aspects of the building far sooner than with traditional methods.

Table 2 – Different construction method requirements (Fawcett et al. 2005)

For the purpose of this research question, the four key advantages of OSM that will be discussed are: Cost, Time, Quality and Environmental Impact.

A true cost comparison between OSM techniques and traditional techniques is difficult to achieve due to the vast differences of the respective methods. Factors such as economies of scale, reduced waste and improved quality, all have direct links to the overall costs and current literature tends to be biased. Taylor, (2009) explained that during procurement stages, due to a lack of understanding many industry professionals often don’t take into consideration any of OSM’s cost influencing factors such as shorter delivery times, erection times, reduced site storage and reduced welfare facilities. Another aspect frequently overlooked, is the higher build quality achieved by using OSM, requiring virtually no snagging on site and defects are highly unlikely. Factory controlled conditions allow work to be done 24/7, with no downtime for adverse weather conditions. With traditional building methods, weeks of on-site labour are often lost due to bad weather conditions. This in turn causes projects to fall behind schedule resulting in additional costs. These factors, combined with simultaneous on-site and off-site work, increase productivity and promote vast cost savings using OSM.

A study conducted by Shahzad et al. (2015) compared 18 similar housing developments in New Zealand, some that used OSM techniques, and some that utilised traditional techniques. It was found that the cost savings from using OSM over traditional techniques was 19% on average whilst a cost saving of 24% was achieved in relation to the development of affordable homes. It could be suggested that the additional savings on affordable homes might be due to a more simplistic design.

Shahzad et al. (2015) stated that OSM not only saves on construction costs but also offers a more reliable estimate of the upfront costs, total investment required and the overall return on investment.

The research conducted by Shahzad et al. (2015) also found that using OSM over traditional methods achieved an overall time saving of 34% on average and 50% on affordable homes. Again, this could be a result of the simplistic designs utilised for affordable homes. It is considered by many professionals that the pre-construction design stages, when using OSM, are more time consuming. However, if additional design details were to take longer, this could possibly be off-set with an expedited construction time.

Taylor, (2009) identified that the duration of each OSM technique varied with the complexity of each project and the number of components produced in a factory. However, the actual time spent on-site during the construction was considerably lower with OSM techniques which was confirmed in statistics provided by Fawcett et al. (2005) in Figure 6.

An example given by Taylor, (2009) regarding OSM, that involved less on-site time was demonstrated by McDonalds fast food chain. Their projects can go from green field site to the sale of food in as little as 48 hours. McDonalds was one of the first corporations to utilise MMC techniques. The production of their factory built, building components took less than half a year with the help of standardised designs and economies of scale.

Figure 6 – On-site Construction Time, (Fawcett et al. 2005)

According to Mishra, (2012) higher quality developments are an undisputable aspect surrounding OSM. It was indicated that the definition of quality in construction defers slightly to the definition offered in the product industry where one product can be considered better quality than another. To an extent, this can also be said for quality in construction. However, quality in construction can also be measured by the conformity by which specifications and government regulations are met.

Wall, (2003) stated that the manufacturing processes used in OSM favours quality due to a process of specialisation whereby the processes are separated into tasks. After the completion of each task, quality checks are done before moving on to the next task. As quality control data is collected, the need for on-site visits from local authorities and private warranty providers can be eliminated or reduced. Hence, decreasing costs in the long run. This process of production is also believed to greatly improve health and safety, (Taylor, 2009).

Taylor, (2009) also explained that the process of OSM utilises modern machinery such as Computer Numerical Control (CNC) systems and laser cutting, which can work to tolerances of less than 0.1mm. With the help of 3D models and virtually tested components, problems that might arise in the future could be eliminated.

A report published by UKGBC, (2014) stated that 400 million tons of materials were delivered to construction sites each year of which 60 million tons were thrown away due to over ordering and damages caused during storage or transport. The construction industry as a whole is said to produce around 109 million tons of construction waste each year, equating to around 3 times more waste than all UK households combined. These figures were derived from statistics published by UKGBC in 2014 and could be considerably more in the current years.

Pan, et al. (2009) explained that despite these alarming figures, the construction industry is making significant steps to reducing waste, partly driven by the increased taxes on landfill. However, the authors continued to state that off-site factories are still far better suited to reducing waste and recycling un-used materials than building sites. Materials in factories are stored in controlled conditions and quantities are calculated more accurately. A report by Keal, (2007) based on an investigation conducted on OSM manufacturers, concluded that the use of modular OSM could produce less than 1% wasted material. This confirms other literature such as Khalfan et al. (2014) and Kelly, (2007) who claimed that OSM could reduce waste ranging from 50% to 90%.

Further consequential benefits of OSM discussed by Ermolli (2015) included an estimated 50% reduction of water usage on-site compared to traditional methods by reducing the need for wet trades. These benefits combined with the reduction of waste, the increased use of recycled materials and an improved overall quality, enables manufacturers to develop homes that produce 60% less CO2 emissions than traditionally built houses during the building’s lifecycle.

An interesting aspect considered by Ermolli, (2015) is the possible re-utilisation of prefabricated elements. The use of OSM promotes the concept of de-construction whereby each element of the house could, in-theory, be taken apart and be put back on a lorry, as individual components the same way it arrived on-site.

Health and Safety is a major issue associated with traditional construction approaches (Taylor, 2009). The UK is considered to be one of the world’s leaders in reducing construction related accidents (HSE, 2017). The combination of the large number of sub-contractors who work on-site alongside each other, coupled with poor weather conditions, working at height and the use of heavy machinery, means workers continue to be at risk. Myers, (2013) stated that this is in contrast to OSM methods, which use a specialist workforce in a controllable environment, and reduces time spent on-site. This is supported by a report, published by the HSE, (2016). Comparing Health and Safety in the construction sectors and in the manufacturing sectors, reporting that in 2016, 43 fatalities occurred in the construction industry whilst only 27 occurred in manufacturing industries.

The disadvantages associated with OSM are broad and vary between different literature sources. However, one common element suggested is that OSM is still battling against its tarnished image from the post-war era. An improvement came in recent years when mortgage providers started to accept ‘pre-fab’ houses for financing plans which opened OSM to a greater market share.

Ezcan et al. (2013) conducted research into the opportunities surrounding current OSM techniques and identified the main disadvantages that will be discussed in the following sections.

The use of heavy machinery, intricate design and 3D modelling from the on-set of the project is considered to be a deterrent for many industry professionals during procurement selection, (Taylor, 2009). Traditional methods often allow for on-site construction to begin whilst design details are being finalised. With a large proportion of cost commitments early-on, developers have less scope for postponing expenditures and improving their cash flow. Although the overall project costs are considered to be lower with OSM, the early client commitment in a fluctuating economic market could be seen as a disadvantage.

Many of the large developers use standardised designs, which cannot be transferred and used for OSM houses due to the nature of the unique manufacturing processes. Therefore, new designs and new standardisation are required. Design philosophy has been built around traditional building methods and Ezcan et al. (2013) noted that the majority of designers in the industry have very little expertise in designing OSM building components. The same could be said for contractors responsible for implementing the designs and components on-site; this lack of knowledge has resulted in OSM designs having a reputation of being aesthetically poor and appearing ‘boxy’ (Taylor, 2009).

A further issue discussed by Schoenborn et al. (2012) is that OSM does not allow for easy design changes once manufacturing has begun. Changes may be impossible, costly and could affect the overall structure of the building. This could, however, promote a more meticulous pre-construction design process, that could eliminate the need for design changes at later stages of the project, which are costly, even using traditional techniques.

Smith, (2015) identified transportation as one of the biggest limitations affecting OSM. Transportation by road is currently the only option for getting materials and components on-site. Therefore, vehicle sizes can restrict design configurations and hinder the use of large spans. Once the components, panels or modular sections, have arrived on-site, cranes are required to lift them into position.

Taylor, (2009) stated that the construction industry is dominated by small firms. Currently there are only a few OSM suppliers and manufacturers in the UK. If components need to travel greater distances, the likelihood of damage during transport is significantly increased. Damaged goods could increase costs and cause immense delays that would drastically affect the tight schedule that makes OSM an attractive building method. With the use of traditional methods, a delay or damaged materials can typically be rectified in a short amount of time.

Specific advantages and disadvantages surrounding OSM are difficult to quantify due to the unique nature of every construction project and the different approaches used by each developer. According to literature the advantages of OSM can be found in greater control of quality in the production phase, a reduction of waste material on-site and off-site and a more energy efficient final product. Reduced construction times and reduced labour costs improve profitability and productivity for developers. This, combined with an increased guarantee on final quality for buyers and a greater upfront cost certainty for developers would make OSM seem like an obvious choice for most involved in the housing industry. However, there are many other external factors that create barriers such as the initial high costs and the lack of design flexibility together with the above identified design limitations due to transport restrictions.

These disadvantages currently might prevent OSM from becoming a leading building method and are likely to be linked with the lack of understanding surrounding this new construction technique. The literature review indicated that attitudes in the construction industry require changing in order for OSM to achieve its full potential.

As previously defined by Windle (2004:2), traditional construction methods can be described as buildings with cavity walls and a timber supported pitched, tiled or slated roof. This method of construction has dominated the industry for a number of centuries and there has been very little change. De Vries, (2006) indicated that trades such as bricklayers still use the same set of tools as they did centuries ago.

Unison, (2006) suggested that over the last decade, traditional building methods have developed into a method known as ‘rationalised traditional method.’ Previously, this term described the discovery and use of cavity walls, insulation and manufactured bricks. Nowadays, it comprises a combination of traditional methods and OSM components such as roof structures, stair structures, flooring systems and even plumbing and electrical solutions; all created to improve productivity of traditional building methods. Due to the vast amount of time spent refining traditional methods with continuously updated building regulations and individual product standards set by the government, this technique has become well established within the industry. In essence, when building regulations are met and signed off by local authorities, a building is considered to be adequate and can be sold.

Evans, (2016) explained that developers have become extremely efficient at using traditional methods and continue to work within their comfort zone, which can be very profitable when done correctly. Many owner’s of development companies or people who have worked their way up the corporate ladder have a trade backgrounds in traditional methods, thus potentially limiting their knowledge to the tried and tested methods they have adopted throughout their careers. Their current lack of knowledge surrounding MMC and the risks involved with a complete change in the design and build process could explain why traditional methods continue to dominate the housing industry. However, when disregarding aspects such as time, quality and cost, other present factors that affect traditional building methods, such as the current skilled worker shortage, as suggested by CIOB, (2013) have a direct effect on the increasing cost of labour.

An underlying issue discussed by Dickens, (2017) stated that 97% of the construction industry is made up of companies with fewer than 14 employees. These companies follow trends in the industry and therefore, without a drastic change by the leading developers in the UK, the industry will not accept OSM as a leading building technique.

An investigation into the barriers facing OSM in the Chinese construction industry was conducted by Mao et al. (2015) who found 18 critical factors and identified the top 3 as: the absence of government regulations and incentives, lack of industry supply chain capable of delivering OSM products and the fluctuating market demand. These issues can be related directly to the UK industry and are being addressed by the proposed UK government white paper as suggested by Leech, (2017). The barriers OSM face will be explored further using primary data.

The literature surrounding OSM within the housing industry is heavily detailed with abundant sources of information. However, there is little literature available relating to the solution of introducing OSM to current developers, bridging the knowledge gap and changing the public image associated with OSM.

Most literature identified the need for change within the industry and some suggested that changes are taking place. However, it could be said that change is happening through foreign investments that are capitalising on the UK’s inefficient housing industry. In order for OSM to achieve its full potential, the knowledge gap and the social and political acceptance of OSM needs to be addressed. The current literature suggested that the key issues preventing the wider uptake of OSM were its increased upfront costs, lack of experience and that a change in the use of construction method could put many companies out of business.

According to literature, OSM is a technique that many regard as the future of the construction housing industry; large investments are being made into factories following the success seen in other countries (Leech, 2017). The purpose of this chapter is to identify and propose the methodology most suited to providing primary data to support and criticise the stated research objectives.

Qualitative research was chosen over quantitative research to gain an insight into the current views of industry professionals. A detailed case study on projects that utilised OSM has been provided to compare with findings from the literature review and interviews.

Fellows and Liu, (2008) suggested that the success of the dissertation research can be measured against whether it provided further information to support current industry theories and literature.

An evaluation of the literature review identified a range of clear benefits associated with the use of OSM with only a few negative implications that could be overcome with a better understanding of OSM. Despite these findings, current literature also identified that OSM only equated to a small proportion of the industry and has seen very little growth over the last 8 years. These contradictory findings highlighted the need to undertake primary research in order to assess the views surrounding OSM from industry professional’s perspectives. Further investigations were made to gain a greater understanding as to the reasoning behind OSM’s minimal market share and how industry professionals see the housing industry developing in the future.

The purpose of this dissertation is to investigate the current use of OSM and the factors that may prevent it from becoming a leading building technique in the UK housing industry. In order to gain relevant primary data, the objectives outlined in section 1.2 were used to assist in developing the research questions.

There are two categories of data collection, identified by Kothari, (2004) as primary and secondary. To conduct a successful investigation and to ensure it remains as relevant and legitimate as possible, a combination of primary and secondary data was used. An overview of each method is given below to facilitate a clear understanding of what part each method contributed during the exploration of the research question.

Naoum, (2013) described primary data as fieldwork research. It is considered to be a process of gathering data that does not already exist but can be collected through a variety of techniques such as interviews, case studies and questionnaires. Primary data can be categorised into quantitative and qualitative research; each of these has their own unique benefits and will be discussed further in the following chapters. For this dissertation, interviews were the main approach for collecting primary data and are categorised under qualitative research. Interviews are a suitable method used to ascertain the specific views of construction professionals to help bridge the knowledge gap that has been identified in current literature. (reference)

Naoum, (2013) described quantitative research as objective in nature as it aims to collect factual data from a large sample of individuals. Questionnaires are the most commonly used method of quantitative research; the use of multiple choice questions gives the ability to statistically collate and analyse data allowing trends to be identified easily (Dube, 2010). This data can then be compared to findings from the literature review. An advantage is the lack of bias from the researcher, however, Naoum, (2013) stated that quantitative data can often lack validity and there is no way of telling how truthful a respondent is or how much thought has been put into each answer. McMillian & Weyers, (2010) explained that to improve validity of results and to be able to see reliable trends, a large sample of individuals must participate.

Fellows and Lui, (2008) defined qualitative data collection as a form of primary research that is based on people’s perceptions as opposed to quantitative research which is based on factual data. It is used to gather views and opinions of selected individuals with specialised knowledge in a chosen subject. Naoum, (2013) considered this type of data ‘subjective in nature,’ as it is dependent on an individual’s point of view allowing the researcher to gain a greater understanding of a certain subject matter. The purpose of this research question was to gain a greater insight into the views of construction professionals surrounding OSM and the barriers it currently faces in the UK; therefore qualitative research was used to provide primary data for this dissertation. The most commonly adopted approach for qualitative data collection is the use of interviews due to its exploratory nature (Curry et al. 2009); and was the method used to gain primary data for this dissertation. Qualitative data is less easy to analyse statistically than quantitative data and requires more filtering, sorting and various manipulations before analytical techniques can be employed (Silverman, 2013). However, the benefits of qualitative research are the extent and depth of the attitudinal responses received, which allow for greater exploration into the research topic.

Naoum, (2013) described secondary data as research that is conducted using existing sources of information; commonly referred to by the author as a ‘desk top study’ due to the nature in which the data can be accessed. Data can be collected from a variety of sources such as books, journals and reports that are available online or within academic institutions. Secondary data was used to form the basis of the literature review and contributed in conjunction with primary data to form a detailed case study. Some limitations arising from the use of secondary data were identified by Kothari, (2004) as reliability, suitability and relevance, these limitations are discussed further in the following chapters.

Following the development of the literature review, the use of interviews was seen as the most appropriate way of collecting primary data. Naoum, (2013) stated that interviews are used to support the research question when the following circumstances exist:

I. When questions require an explanation, rather than just yes or no.

II. When a case study needs to be investigated in detail, asking questions such as how and why things happened the way they did.

Both of these circumstances were applicable for this dissertation question and will achieve the objective of collecting the opinions of industry professionals on OSM’s current use, future developments and the challenges it faces.

A correct interview technique and structure is essential as the quality of the data collected is dependent on it. The interviews allow primary data to be collected only from individuals who are knowledgeable in the subject area. Naoum, (2013) noted that there are three types of interview structures:

i. Structured – This approach asks a consistent set of questions to all interviewees.

ii. Semi-structured – This approach uses a number of pre-determined questions but allows for further questions/discussion to develop of the conversation.

iii. Unstructured – This approach is used when little is known about the subject and information collected shares no consistency with information gathered from other interviewees.

Interviews for this dissertation were to last 20-30 min and to be a combination of structured and semi-structured, dependent on the knowledge of the interviewees.(reference) This interview technique enables the interviewer to gauge the interviewee’s responses and ask specific questions in order to further expand on particular areas. All interviews were transcribed and can be found in Appendices A-D.

.

Prior to the interviews being carried out, a pilot interview was conducted allowing the interviewer to assess whether the selection of questions were broad enough and sufficiently open ended to prompt further discussions. Any issues that arose in the pilot interview were addressed, so improvements could be made ahead of the final interviews.

There are limitations to all data collection methods which must be addressed to reduce the impact on both, the study and the legitimacy of the results. A number of limitations are identified by Kothari, (2004), the ones affecting interviews the most, are explained below.

Biased and false information is one of the most important limitations to take into consideration; often interviewees can fabricate answers to questions they do not have a good understanding about. To minimise this risk, the interviewer needs to have developed a thorough understanding from the literature review and, through conducting similar interviews, should hopefully be able to determine any false or fabricated answers.

Another limitation arising from the use of semi-structured interviews is that the level of detail from the given answers is neither restricted nor controlled. To overcome this problem and avoid any details being missed by the interviewers, Naoum, (2013) stated that a recording should be taken of each interview, with the consent of the interviewees.

Due to time restrictions, the size and extent of the sample of interviewees was limited. Conducting interviews is a time consuming data collection method and therefore it was not possible to carry out a large sample across the entire industry. A smaller sample, ultimately does not represent the views of the entire industry and, therefore, may have implications for the validity of results.

The process of collecting primary data is time consuming due its nature and the level of detail required during the meticulous analysis that is performed on each transcript. Unfortunately, due to time and word constraints, only 4 interviews were conducted for this dissertation. Naoum, (2013) described the process of selecting individuals within the construction housing industry as non-random accidental and purposive sampling. Although some of the interviewees preferred to remain anonymous, details regarding their employment position and experience within the industry were given. Permission was granted from each interviewee for the interviews to be recorded, thus allowing them to be transcribed.

Naoum, (2013) noted that case studies are a form of primary data collection that can provide a descriptive and investigative insight into chosen projects. The purpose of using case studies was to provide working examples of OSM in the housing industry, to be evaluated and compared against the data collected in the literature review and from the interviews. It also aids readers who may not have much knowledge about OSM (Yin, 2009). Two case studies were used for this dissertation and can be found in Appendices E-F:

Case 1: A zero energy, affordable housing project

Case 2: A bespoke, zero energy home, built for the high end market

Both developments used panelised construction systems known as SIP’s (Structural Insulated Panels)

Information used for these case studies was obtained through secondary sources; it was attempted to conduct an interview with both companies involved, however, both declined to answer any questions.

It is stated by Yin (2009) that, as with any data collection method, there are a number of limitations to consider when adopting a case study approach. Firstly, a few case studies do not reflect an entire industry and therefore the problem of generalisation needs to be carefully monitored. The case studies provided in this dissertation tried to reflect different sectors within the OSM market to help improve validity. Another limitation mentioned by the author was that the secondary data used to produce the case study may be biased, the information shared may only be the information the company wants you to know and may not highlight any problems that were encountered during the project.

The process of data analysis adopted for this dissertation is derived from a wider theory known as the Grounded Theory, developed by Glaser and Strauss, (1999). The process of this theory is considered to be an appropriate method of analysing qualitative research. Initially, the recorded interviews were transcribed and the data was coded; a process identified by Naoum, (2013) which allows the collected data to be categorised by noting reoccurring trends and themes. The notes are known as codes and were used to generate the chapter headings in the Analysis of Results.

These results were subsequently compared to the findings from the literature review and the case studies; a process known as triangulation (Naoum, 2013) and used to enhance the accuracy and reliability of results. Fellows and Lui, (2008) stated that this enables the researcher to reduce limitation issues whilst exploiting the advantages of all the research techniques used.

A qualitative data collection approach was chosen as most suitable research for this dissertation together with several semi-structured interviews with a range of industry professionals to gain opinions and insight within the given time frame. The data collected was reviewed and compared to the findings of the case study, to determine whether the benefits of OSM could make it a practical alternative to traditional construction methods in the UK housing industry. A coding technique was used to analyse the results of the interviews allowing for triangulation with current industry literature.

This chapter contains a detailed analysis of the results gained from primary research. A number of interviews and two case studies were conducted to ascertain the views and opinions of industry professionals and to gain information on projects that have utilised OSM in order to compare it with the information found in the literature review to see whether the findings correlate. The results gained in this chapter are intended to support the research aims and objectives that will be discussed at the end of this dissertation.

The consensus from the literature review showed that there are numerous benefits that arise through the use of OSM, however, the uptake of OSM has been slow. There are various large organisations investing heavily into OSM but there are still a number of barriers across the industry. The aim of the interviews was to gather the opinions of a variety of construction professionals from director to architect, to discover if their views supported the findings of the literature review.

Each interview was labeled A to D (Appendices A-D) for easier referral and a profile summary was obtained for each interviewee. The interviews were either semi-structured or structured dependent on the knowledge of the interviewee and included questions which had been derived from the analysis of the current literature surrounding OSM. The 4 interviewees were:

(A). Company Director: Director of the UK division of one of Europe’s leading OSM companies, specialising in mid to high end housing market with the use of a bespoke closed panel construction technique.

(B). Property Developer: Longstanding owner of a development company, building mid to high end homes using traditional techniques with limited experience using OSM.

(C). Commercial Director: Employee of high end property development company with some experience using OSM.

(D). Architect: In-house architect for one of the leading high-end housing developers in the UK.

The following chapter headings were derived through a process of coding, which categorises reoccurring themes and trends from the transcribed interviews.

All 4 interviewees shared a common view in relation to the advantages that arise through the use of OSM. Interviewee A stated that moving the majority of labour intensive work into a factory environment produces results that are simply not achievable through traditional techniques. His explanation

(A) “Because of the higher quality, there is virtually no snagging or defects, which is often forgotten when comparing between traditional and OSM.”

supports the findings in the literature review by the likes of Taylor, (2009) who suggested that working in factory controlled environments would lead to improved quality and fewer defects.

Interviewee A also specified that once their homes have been built in the factory, they could be erected on site within 3 days, provided all necessary groundwork had been completed. This is partly supported by interviewee D, although his experience with OSM was limited to sub-assemblies and components:

(D)”I believe it greatly reduces the time required on site. For example, the pre-made floor joists we use can be hung and decked out within 2 days with a smaller workforce. Before, this would take up to two weeks.”

The limited experience of OSM by Interviewee B did not allow him to offer many details for the advantages and disadvantages surrounding OSM but his perceived thoughts matched the conclusions from the literature review:

(B)”Speed of installation and improved quality of finish.”

Interviewee C also confirmed the findings by Khalfan et al. (2014) and Kelly, (2007) that using OSM could reduce waste by up to 90% and is better suited to recycling un-used materials. He also supported findings from Ermolli’s (2015) that estimated a 60% reduction of CO2 emissions during the building’s lifecycle could be achieved through OSM’s improved quality.

(C) “It’s my understanding that OSM reduces waste as quantities are calculated far more accurately and the working tolerances are far less. At the same time un-used materials can be recycled and used again. A higher quality house also improves its energy efficiency which reduces Co2 emissions and the cost of running the house.”

Interviewees B, C and D all identified similar disadvantages as the ones stated in the literature review by the likes of Ezcan et al. (2013) and Taylor, (2009) such as design limitations, increased need for planning and scheduling, meticulous design work, transportation restrictions and that OSM is perceived to be more beneficial for multiple dwellings rather than a smaller number of units. However, interviewee A contradicted this by stating that their OSM homes push the boundaries of design and can produce bespoke singular homes although he highlighted the dependence on traditional methods to produce the sub-structure. A setback or a fault in the groundworks could result in vast delays and logistical problems.

All interviewees had similar opinions on the barriers that are affecting the growth of OSM in the UK, despite their different levels of experience. All agreed that the requirement of large investments and the uncertainty of future demands were the biggest barriers currently facing OSM. The literature review clearly supports this point of view, highlighting the associated costs of OSM with reference to the large investments made by the likes of Laing O’Rourke and Legal and General Homes. Interviewee A specified:

(A) “Developers need to invest heavily into factories and the fluctuating market and scare of another recession puts them off, factories require continuous output to be profitable. Developers have very few employees, relative to overall revenue because all works are subcontracted out. Therefore, if demand falls, output can also fall without having to reduce number of employees, simply build less houses with fewer contractors.”

Confidence within the industry would appear to be relatively low as all interviewees gave a similar responses in regard to the fluctuating demand and the fear of another recession. Interviewee C explained:

(C) “’I believe that the industry still suffers from confidence issues, too often companies increase their staff, invest heavily and then see it all come crashing back down during the next economic recession. This nervousness prevents companies from investing millions into factories and new technologies. I think there are many companies that would love to move into the OSM market but it’s too much of a risk for them at the moment.”

However, interviewee C goes on to suggest that there are different ways to access the OSM market such as through the supply chain.

(C) “There are two difference routes into OSM, one is with significant investment into factories and the other is through a collaborative effort through the supply chain.”

When asking interviewees whether OSM manufacturers in the supply chain could help the growth of new technologies by providing a solution for developers that are reluctant to invest but wish to use OSM, interviewee A stated that:

“Developers want to have unique designs and ideas, they don’t want to be limited or controlled by anyone else. Other companies could undercut them or get preferential treatment. Current methods allow full control over the entire process.”

Another barrier identified in the literature review by Evans, (2016) was the lack of knowledge surrounding OSM. Interviewees (B) and (C) supported this finding:

(B) “Developers are very much set in their ways of working. A perception that OSM benefits are for multiple dwellings in a pod format, and not a smaller no of units.”

(C) “Infrastructure around the industry is structured around traditional building techniques and there is limited knowledge within companies surrounding OSM. I think more reports, case studies, TV shows and availability will slowly increase the popularity of OSM.”

When asked whether the history of OSM and its previously tarnished image might still affect the public’s perception on homes built using OSM, it was clear that none believed this to be true. Interviewee’s (A) challenged anyone who believes OSM to be of lesser quality to take a look round their show homes or their factory. Interviewee (B) supported this claim by suggesting that the public has understood the benefits of a lower ‘U’ value which is achieved through a greater quality and can reduce the cost of running the building.

When asked about what incentives are thought to be required to promote the use of OSM, the answers from all respondents were fairly consistent. A need for change was identified by all interviewees and confirms Sweet’s, (2015) findings that in countries such as Sweden and Japan, earthquakes and freezing winters have already created a need for change.

Although reduced time, cost and emission targets look to help promote the use of OSM, interviewee (D) suggested that new standards for quality and performance need to be set in order to truly promote the use of OSM.

(D) “There needs to be a greater need for change. I think once it gains momentum, a lot of companies will jump on so that they don’t get left behind. I think the change has already started, it just needs a little push from the government maybe. Perhaps setting new standards for quality and performance of the building that are barely achievable using traditional techniques would help. And maybe some serious investment into supply chain and developers to help them get started.”

(C) “The change needs to come from the government as companies are content with the way they are working.”

As Interviewee (A) stated, without a need for change in the UK, the use of OSM may not increase drastically.

(A) “I think it requires a need for change! I think the skill shortage and the lack of young people entering the industry is one of the causes for need of change. The new government white paper sets out targets for the industry by 2025; I think to reach these targets OSM will be required.”

The key targets the government plans to achieve by 2025 are to reduce overall cost of construction and the whole life cost of built assets by 33%, reduce overall construction duration, from inception to completion by 50% and to reduce green house emissions from the built environment by 50% (Leech, 2017). These targets all relate to the previously identified advantages of OSM with similar figures provided by the likes of Shahzad et al. (2015). Additionally, this can be linked to Brandon Lewis’s stating companies need to utilise OSM if they don’t wish to be left behind. In order to support the industry to achieve these targets, interviewee A clarified:

(A) ‘The government is also making more funds available to help companies getting involved with OSM.’

The current skill shortage was mentioned by all interviewees as a current driver for the use of OSM. This supports the findings from Leech, (2017) that the skill shortage is a consequence following the recent recession and continues to increase the cost of labour. Interviewee (A) acknowledged:

(A) ‘With the current skill shortage and new government incentives, more and more will start using OSM.’