Top Essay Writers

Our top essay writers are handpicked for their degree qualification, talent and freelance know-how. Each one brings deep expertise in their chosen subjects and a solid track record in academic writing.

Simply fill out the order form with your paper’s instructions in a few easy steps. This quick process ensures you’ll be matched with an expert writer who

Can meet your papers' specific grading rubric needs. Find the best write my essay assistance for your assignments- Affordable, plagiarism-free, and on time!

Posted: February 10th, 2024

Table of figures

Contents

Students often ask, “Can you write my essay in APA or MLA?”—and the answer’s a big yes! Our writers are experts in every style imaginable: APA, MLA, Chicago, Harvard, you name it. Just tell us what you need, and we’ll deliver a perfectly formatted paper that matches your requirements, hassle-free.

Absolutely, it’s 100% legal! Our service provides sample essays and papers to guide your own work—think of it as a study tool. Used responsibly, it’s a legit way to improve your skills, understand tough topics, and boost your grades, all while staying within academic rules.

Our pricing starts at $10 per page for undergrad work, $16 for bachelor-level, and $21 for advanced stuff. Urgency and extras like top writers or plagiarism reports tweak the cost—deadlines range from 14 days to 3 hours. Order early for the best rates, and enjoy discounts on big orders: 5% off over $500, 10% over $1,000!

Descriptive statistics: frequency tables for survey responses

Graphical comparison of medical student and foundation year doctor survey responses

Yes, totally! We lock down your info with top-notch encryption—your school, friends, no one will know. Every paper’s custom-made to blend with your style, and we check it for originality, so it’s all yours, all discreet.

Qualitative data: free text responses

No way—our papers are 100% human-crafted. Our writers are real pros with degrees, bringing creativity and expertise AI can’t match. Every piece is original, checked for plagiarism, and tailored to your needs by a skilled human, not a machine.

We’re the best because our writers are degree-holding experts—Bachelor’s to Ph.D.—who nail any topic. We obsess over quality, using tools to ensure perfection, and offer free revisions to guarantee you’re thrilled with the result, even on tight deadlines.

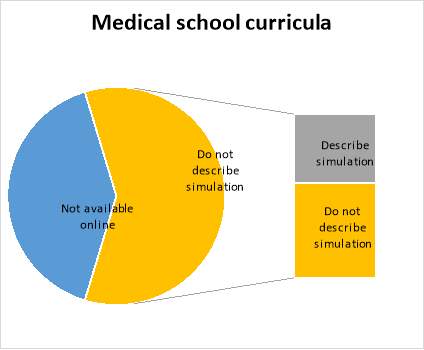

Figure 2. Medical school curricula detailing use of simulation as a teaching and learning method

Figure 3. Thematic units from content analysis of the literature weighted according to frequency

Our writers are top-tier—university grads, many with Master’s degrees, who’ve passed tough tests to join us. They’re ready for any essay, working with you to hit your deadlines and grading standards with ease and professionalism.

Always! We start from scratch—no copying, no AI—just pure, human-written work with solid research and citations. You can even get a plagiarism report to confirm it’s 95%+ unique, ready for worry-free submission.

In a climate of increasing attention to patient safety, medical graduates must be primed to manage clinical emergencies before they are required to initiate treatment whilst alone on call. Simulation is an apt teaching tool to provide undergraduates with opportunities for deliberate practice thus facilitating their development into prepared foundation doctors. This study sought to develop a simulation curriculum for medical students in Practical Emergency Care by combining quantitative and qualitative methods of enquiry. The authors reviewed medical school curricula and the literature, as well as surveying medical undergraduates and foundation doctors. Findings include a discrepancy between the sparse advertisement of simulation in medical school curricula (only 8 of the 19 curricula available online describe simulation among their teaching methods) and the growing body of literature detailing clinical content, nontechnical skills, and execution of simulation scenarios. 6.53% of medical students and 5% of foundations doctors responded to surveys, chiefly with requests for more simulation. Both groups of respondents selected scenarios involving clinical and nontechnical skills, as well as trauma and unresponsive patients. However, the two groups disagreed as to whether subsequent scenarios should involve human factors, and common or rare scenarios. The study findings are used to determine what clinical scenarios and nontechnical skills should be incorporated into a working model curriculum as well as generating several recommendations for future enquiry.

There is mounting evidence that UK medical school curricula do not adequately prepare undergraduates for foundation training,(1) with medical students receiving minimal teaching in acute and traumatic aspects of care.(2) Despite calls for its mandate by the Quality Assurance Association for Higher Education (QAAfHE)(3) and the General Medical Council (GMC),(4) there is no standardised programme of preparation for managing acute medical emergencies, such that foundation doctors are confronted with emergencies that overstretch them.(1) Indeed, the QAAfHE Subject Benchmark Statement for Medicine states that ‘Graduates must be able to recognise and carry out the initial treatment of the following emergency situations, which require immediate action, such as: cardiac arrest; anaphylactic shock; the unconscious patient.’(3) The GMC and Department of Health have called on medical schools to employ new technologies among their educational arsenal and have students practice in a simulated environment before clinical reality.(5, 6) Simulation has repeatedly been proven as an effective teaching method and arguably there is no teaching tool better placed to reconcile the needs of medical students as adult learners with the demands of the modern healthcare environment where patient-safety concerns(7-17) and resource-restriction(9, 11, 15, 18, 19) are ubiquitous. Simulation has been proven uniquely capable of satisfying multiple simultaneous teaching and learning needs. It can facilitate opportunities for reflective practice(7, 9, 10, 13-15, 20-26) and develop confidence(18, 25-30) as well as increase learners’ perceptions of their own readiness for clinical practice.(7, 9, 31) Simulation is an adept tool for developing team communication skills.(9, 16, 25, 32-34) Not only has the utility of simulation for ensuring clinical competency been proven,(8, 9, 14, 15, 18, 21, 25, 35, 36) but perhaps most importantly, as a cornerstone of modern adult learning theory,(37) learners themselves perceive simulation as useful and relevant.(7, 11, 18, 38-41)

You bet! From APA to IEEE, our writers nail every style with precision. Give us your guidelines, and we’ll craft a paper that fits your academic standards perfectly, no sweat.

The aim of this study was to contribute to improved relevance and efficacy of the undergraduate medical curriculum and thus better prepare final year medical students for independent clinical practice. The objectives to achieve this aim were to develop a simulation curriculum for medical students in Practical Emergency Care using a mixed methods approach and to synthesize four simulation sessions to be undertaken by medical students during their final year Emergency Medicine placements at the University of Manchester.

This quantitative and qualitative study comprised several elements including review of UK medical school curricula and programme specifications, literature review, and surveys of medical trainees at both undergraduate and postgraduate level.

Curricula and programme specifications for all 32 medical schools in the United Kingdom were accessed via the internet on 17th May 2017. Those publicly available were reviewed for reference to ‘simulation,’ and positive results were contacted via email with a request to provide further detail on how simulation is used to teach acute medical emergencies to their final year students.

A three-stage search of the literature was conducted comprising an initial broad search including grey literature, followed by a PubMed search on 19th May 2017 using the search criteria ‘simulation AND undergraduate AND emergency medicine,’ which generated 94 articles published since 2010. Exclusion criteria entailed articles focused primarily on postgraduate or preclinical undergraduate studies; students of Dentistry, Veterinary Science, and Nursing; simulation used as a tool primarily for assessment rather than teaching or simulation used to teach specialties other than Emergency Medicine; as well as virtual simulation. Identical searches were conducted in Medline, EMBase, and Cochrane and the same exclusion criteria applied. The remaining papers were categorised as reviews, meta-analysis, or descriptive studies so that the bibliographies of the 14 reviews, meta-analyses, and best evidence guides therein could be reviewed according to the same criteria to improve catchment and reduce search bias. This generated a final body of 57 papers, which were analysed according to the following themes: what is simulation effective at teaching, what clinical scenarios and other skills should be included in the curriculum, and how should the scenarios be executed.

Yep! Use our chat feature to tweak instructions or add details anytime—even after your writer’s started. They’ll adjust on the fly to keep your essay on point.

Figure 1. Three stage literature search; search terms: ‘simulation AND emergency medicine AND undergraduate;’ exclusion criteria: ‘postgraduate, preclinical undergraduate, Dentistry, Veterinary, Nursing, computer-based simulation, simulation used solely to assess

Surveys were constructed to pool opinions from medical students in their clinical years of study and foundation doctors anonymously. They were mapped to the University of Manchester curriculum and checked by a consultant for content validity. They were piloted before distribution to medical students at the University of Manchester via OneMedBuzz the official platform and related social media pages, whilst foundation doctors working across the North West received the survey via the Health Education England administrator. All medical students and foundation doctors were sampled to mitigate the anticipated low response rate. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected via Surveymonkey. The data was analysed in SPSS to create tables of descriptive statistics for numerical summary, as well bar charts for visual comparison of medical student and foundation doctor opinions. The data also underwent chi-square testing to demonstrate independence. Free text answers were included to improve content validity and these underwent content analysis to elicit themes that could be used to contextualise and inform quantitative data.

All methods detailed above were collated to synthesize four practical sessions according to best practice.(42)

Easy—place your order online, and your writer dives in. Check drafts or updates as you go, then download the final paper from your account. Pay only when you’re happy—simple and affordable!

Medical school curricula and programme specifications were reviewed to delineate the extent and methods by which simulation is currently employed as a teaching tool in the UK and to inform curriculum design. Of 34 medical schools in the UK, 2 were excluded as they do not offer clinical medicine. 19 curricula and/or programme specifications were available for open access via the internet. 13 were not available or had been temporarily removed pending review. Of the 19 accessed on 17th May 2017, 8 (42%) described using simulation as a formal component of the taught course and so a request for further detail was submitted via email. Of these eight, two responded with the below:

The literature was analysed to elicit key thematic units which could be correlated with the survey findings to inform curriculum design. The three broad themes entailed learning domains and clinical scenarios for inclusion, as well as how simulation sessions were best executed:

Super fast! Our writers can deliver a quality essay in 24 hours if you’re in a pinch. Pick your deadline—standard is 10 days, but we’ll hustle for rush jobs without skimping.

Clinical scenario Learning domain Execution

Chest pain and cardiac arrest were the most commonly deployed clinical scenarios (9, 11, 19, 22, 25-27, 36, 41, 43-46), with respiratory,(9, 11, 18, 25, 27, 33, 43, 45, 46) and neurology,(22, 25, 43-47) and surgery(18, 25, 43-46) in tow. The vignettes for each category of clinical scenario were notably diverse, including an overdose of alcohol and prescribed medications presenting with decreased respiratory rate, as well as an agitated postictal head trauma victim presenting then experiencing a further seizure during the scenario.(47) Similarly, the outcomes of the scenarios were intentionally unpredictable,(13, 48) that is, both negative and positive irrespective of the students actions. It is worth noting that cardiac scenarios may be overrepresented as simulation is well established as a tool for teaching ACLS. Simulation was particularly useful for teaching non-technical skills such as team work(9, 13, 16, 19, 22, 23, 25, 33) and clinical reasoning(14, 20, 23, 25, 33, 35, 46) with attention also paid to preparedness for clinical practice in terms of professional communication skills(9, 13, 14, 18, 22, 23, 30, 33, 34, 44, 47) but also affective rehearsal.(9, 31)

There was great innovation and variety in the mode of execution of sessions including students being bleeped unexpectedly to simulation scenarios,(18) simulated night shifts,(35) inter-professional simulation,(22, 32, 33) simulation scenarios integrated within Emergency Medicine placements,(9, 19, 23, 25, 36, 44) and scenarios disrupted by challenging relatives or disgruntled senior staff thus furnishing opportunity to develop advanced communication skills in a controlled environment.(22) There was a discrepancy between simulation used as a discrete event(16, 25, 35, 45, 49) or running longitudinally throughout final year curriculum(9, 19, 20, 23, 25, 36, 44) with learning consolidated by feedback,(24, 25, 27, 42, 50, 51) clinical shifts(19) or subsequent reflection on a real clinical case.(23) Several papers advocated the importance of simulation as a bridge to preparedness(27) rather than a tool for teaching new information, stressing the value of a flipped classroom to familiarise participants with theoretical material and the manikin itself.(9, 16, 18, 28, 36, 52, 53) There was a tension between whether the task ought to be complex to simulate the demands of the clinical environment or simpler in order to allow the learner to focus on mastering basic skills,(9, 10, 54) with some opting to introduce a programme of increasing complexity.(13, 48) It is encouraging in a climate of limited resources that simulation was repeatedly demonstrated to be an effective teaching tool regardless of group size:(19, 25, 26, 55) not only did observes benefit similarly to active participants but they can be engaged in assessment and feedback.(25)

Definitely! From astrophysics to literary theory, our advanced-degree writers thrive on tough topics. They’ll research deeply and deliver a clear, sharp paper that meets your level—high school to Ph.D.

6.53% (96/1471) of clinical medical students and 5% (87/1734) of foundation doctors responded to the surveys. It should be noted that the total population of each group represents a slightly different figure: the total number of medical students in Years 3-5 including 3-4 and 4-5 intercalators is accurate, whereas the total number of foundation doctors will be slightly lower than the total number of foundation posts provided due to vacancies. At the time of writing, the survey of foundation doctors has been open for less time leading to fewer respondents.

The four answers selected with the greatest frequency will be detailed here in accordance with the objective of creating four simulation sessions. Medical students requested learning domains of clinical skills (89.89%), clinical factors (88.76%), human factors (57.3%), and advanced communication skills (40.45%) to be included amongst the simulation sessions. Whereas foundation doctors described feeling most prepared for clinical factors (83.53%), followed by advanced communication skills (76.47%), clinical skills (71.76%), and prescribing (68.24%); and least prepared for human factors (47.76%), clinical skills (41.79%), prescribing (40.30%), and advanced communication skills (29.85%). 71.76% foundation doctors felt prepared for clinical skills and 76.47% foundation doctors felt prepared for advanced communication skills. One medical student provided a free text answer requesting sessions on: ‘clinical prioritisation and triaging leadership and innovation resource allocation major incident planning and resilience.’ Thirteen foundation doctors utilised the free text box to describe feeling prepared for ‘ALS’ and ‘basic skills only,’ but unprepared for ‘wound care and practical prescribing,’ ‘logistics and paperwork,’ ‘[any] of the above,’ ‘trained to do all [of the above] but not much experience,’ ‘pressure of increased workload due to reduced staff levels,’ ‘time prioritization and referrals to seniors,’ ‘management plan,’ ‘communication with colleagues and prioritization.’

The most requested clinical scenarios by medical students were the unresponsive patient (61.46%), sepsis (57.29%), cardiac arrest (51.04%), and trauma (50%), with two free text answers requesting sessions on all survey options, and one respondent requesting anaphylaxis. Again, the answers selected by the foundation doctors both correlated and did not correlate with these as 40.48% felt prepared to manage an unresponsive patient, 96.43% felt prepared for sepsis, 65.48% felt prepared for cardiac arrest, and only 17.86% felt prepared for trauma. The foundation doctors felt least prepared to manage burns (69.05%), intoxicated patients (64.29%), trauma (38.33%), and endocrine emergencies (58.33%). In their free text answers the foundation doctors felt that acute kidney injury, falls, major haemorrhage, electrolyte abnormalities, and self-discharge should also be included. Survey respondents were not asked how the simulation scenarios ought to be executed. Survey responses for learning domains and clinical scenarios underwent chi-square testing to yield Yates corrected p-values of <0.05 for all relevant answers.

Respondents were provided with a final free text box to provide further input into the curriculum. The most frequent answer was ‘more of the above.’ This was followed by requests for general scenarios where many differentials had to be considered and excluded. The next few themes appeared with equal frequency: common scenarios, nontechnical learning including sessions that incorporated handover to seniors, prioritising and escalating patient care. Violence and prehospital triage were also requested. Foundation doctors described feeling poorly prepared to manage traumatic and paediatric presentations. These were followed by acute psychiatry and cardiology, as well as cardiac arrest and chest pain. The 95.96% of foundation doctors who had undertaken simulation training as undergraduates were asked to name a scenario in clinical practice that the aforementioned training had prepared them well for: twenty-eight respondents selected cardiac arrest and chest pain, seventeen chose sepsis, fifteen chose shortness of breath, and nine selected shock. Notably, other respondents described nontechnical aspects of acute scenarios such as remaining calm, working in a team, and remaining focused amid distractions and demands from other health care professionals, as well as communication skills. Foundation doctors fed back that undergraduate simulation should incorporate teaching on altered mental status and common bleeps in a realistic setting i.e. the learner is in role and the scenario is complex, that is, the learner is unaided and the patient does not respond to first line treatment. There were further requests for teamwork and trauma. A small number of respondents suggested that sessions should incorporate prioritisation, handover, and experience of working amid hassle by nurses and real-time impediments including requesting interventions and writing prescriptions.

| Topic | Medical students |

You Want The Best Grades and That’s What We Deliver

Our top essay writers are handpicked for their degree qualification, talent and freelance know-how. Each one brings deep expertise in their chosen subjects and a solid track record in academic writing.

We offer the lowest possible pricing for each research paper while still providing the best writers;no compromise on quality. Our costs are fair and reasonable to college students compared to other custom writing services.

You’ll never get a paper from us with plagiarism or that robotic AI feel. We carefully research, write, cite and check every final draft before sending it your way.