Top Essay Writers

Our top essay writers are handpicked for their degree qualification, talent and freelance know-how. Each one brings deep expertise in their chosen subjects and a solid track record in academic writing.

Simply fill out the order form with your paper’s instructions in a few easy steps. This quick process ensures you’ll be matched with an expert writer who

Can meet your papers' specific grading rubric needs. Find the best write my essay assistance for your assignments- Affordable, plagiarism-free, and on time!

Posted: July 14th, 2022

CHAPTER ONE

Little is known about the psychobiological processes of adults, at age 23, who

We get a lot of “Can you do MLA or APA?”—and yes, we can! Our writers ace every style—APA, MLA, Turabian, you name it. Tell us your preference, and we’ll format it flawlessly.

were born prematurely despite the fact that 1 out of every 9 infants is born too early

(Atzil, Hendler & Feldman, 2011; CDC, 2015; Mannisto, Vaarasmaki, Sipola –

Leppanen, Tikanmaki, Matinolli, Pesonen, Raikkonen, Jarvelin, Hovi, & Kajantie,

2015). Compared to infants born at term, premature infants, face additional obstacles

Totally! They’re a legit resource for sample papers to guide your work. Use them to learn structure, boost skills, and ace your grades—ethical and within the rules.

of immature body systems and more neonatal stress, and are at risk for developmental

delay, and possible parental overprotection patterns (Clarke, Cooper & Creswell,

2013; Grunau, 2013; Kopp & Rethelyi, 2003; Pinquart, 2014).

Starts at $10/page for undergrad, up to $21 for pro-level. Deadlines (3 hours to 14 days) and add-ons like VIP support adjust the cost. Discounts kick in at $500+—save more with big orders!

Developmentally, in the United States, 23 year olds are expected to achieve

independence and form intimate relationships, yet there is limited knowledge about

their emotional intelligence and related psychobiological processes while more is

known about their stress levels, coping strategies, and emotional disorders (Clarke, et

100%! We encrypt everything—your details stay secret. Papers are custom, original, and yours alone, so no one will ever know you used us.

al, 2013; Ingels, Glennie, Lauff, & Wirt, 2012; Pinquart, 2014; Simpson, 2009).

Intrapersonal, interpersonal, adaptability, stress management effectiveness, as well as

general emotional health are all involved in reaching adult developmental milestones

(Granger & Kivlighan, 2003; Simpson, 2009). These important young adults

Nope—all human, all the time. Our writers are pros with real degrees, crafting unique papers with expertise AI can’t replicate, checked for originality.

milestones require the ability to: communicate effectively with others, be sensitive to

others, maintain emotional self-control, use both knowledge and experiences to cope,

manage stress, work and assume responsibilities (Arnett, 2013; Di Fabio & Saklofse,

2014; Simpson, 2009).

Our writers are degree-holding pros who tackle any topic with skill. We ensure quality with top tools and offer revisions—perfect papers, even under pressure.

The abilities required to meet young adult developmental milestones are captured

in definitions of emotional intelligence (EI) and also incorporates the involvement of

the brain’s prefrontal cortex executive functioning which further evolves during this

time period (Kristensen, Parker, Taylor, Keefer, Kloosterman, & Summerfeldt, 2014;

Experts with degrees—many rocking Master’s or higher—who’ve crushed our rigorous tests in their fields and academic writing. They’re student-savvy pros, ready to nail your essay with precision, blending teamwork with you to match your vision perfectly. Whether it’s a tricky topic or a tight deadline, they’ve got the skills to make it shine.

Arnett, 2013; Davis & Humphrey, 2012; Armstrong, Galligan, & Critchley, 2011;

Lishner, Swim, Hong & Vitacco, 2011; Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema & Schweizer, 2010;

Stuss, 2009; Tarasuik, Ciorciari & Stough, 2009; Ciarrochi, Deane & Anderson,

2000). The Hypothalamic – Pituitary -Adrenal (HPA) Axis biological response to

Guaranteed—100%! We write every piece from scratch—no AI, no copying—just fresh, well-researched work with proper citations, crafted by real experts. You can grab a plagiarism report to see it’s 95%+ original, giving you total peace of mind it’s one-of-a-kind and ready to impress.

stress and prefrontal cortex executive functioning abilities are theorized to be involved

with emotional intelligence (EI), functioning, stress, coping, and emotional health

(Frodl & Stuart, & Pretorius, 2007; Smith & Vale, 2006; Herman, Ostrander, Meuller

& Figueiredo, 2005).

Yep—APA, Chicago, Harvard, MLA, Turabian, you name it! Our writers customize every detail to fit your assignment’s needs, ensuring it meets academic standards down to the last footnote or bibliography entry. They’re pros at making your paper look sharp and compliant, no matter the style guide.

Young adults who were born prematurely carry the consequences of their early

birth. As infants, their immature physical systems were responding to ongoing

physical pain from neonatal medical procedures, a longer hospitalization and a

multitude of environmental stimuli with unstable and ineffective bodily system

For sure—you’re not locked in! Chat with your writer anytime through our handy system to update instructions, tweak the focus, or toss in new specifics, and they’ll adjust on the fly, even if they’re mid-draft. It’s all about keeping your paper exactly how you want it, hassle-free.

responses (Grunau, 2002). The foundations for brain growth and functioning and

what will become their usual stress response were being laid at this point in time and

will likely influence lifelong development including meeting young adult milestones.

However, there is a need for research examining the mechanisms of stress and its

It’s a breeze—submit your order online with a few clicks, then track progress with drafts as your writer brings it to life. Once it’s ready, download it from your account, review it, and release payment only when you’re totally satisfied—easy, affordable help whenever you need it. Plus, you can reach out to support 24/7 if you’ve got questions along the way!

relationship with adult emotional health outcome to assure the well being of young

adults and their attainment of developmental milestones (Mannisto, et al., 2015;

Simpson, 2009; Tarasuik, et al., 2009). There is minimal research into emotional

health and its association with biological processes functioning existing to help in

Need it fast? We can whip up a top-quality paper in 24 hours—fully researched and polished, no corners cut. Just pick your deadline when you order, and we’ll hustle to make it happen, even for those nail-biting, last-minute turnarounds you didn’t see coming.

identifying the precise timing and targets of health promoting interventions.

Theoretical Framework

The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) theory of HPA

dysregulation postulates that the stress of prematurity and during early life critical

brain growth periods (i.e. formation completes during young adulthood) effects the

Absolutely—bring it on! Our writers, many with advanced degrees like Master’s or PhDs, thrive on challenges and dive deep into any subject, from obscure history to cutting-edge science. They’ll craft a standout paper with thorough research and clear writing, tailored to wow your professor.

HPA Axis structure and functioning (Eiland & McEwen, 2012; Sullivan, Hawes,

Winchester & Miller, 2008; Barker, 2007; Miller, Chen & Zhou, 2007; De Boo &

Harding, 2006; Pujol, Vendrell, Junque, Marti-Vilalta, & Capdevila, 1993). Stress

responses from the HPA axis are adaptive (allostasis) and if occur frequently,

particularly with prematurely born infants and their underdeveloped systems, will

We follow your rubric to a T—structure, evidence, tone. Editors refine it, ensuring it’s polished and ready to impress your prof.

result in injury or ‘”wear and tear” (allostatic load) on the body (McEwen, 2003 &

2006; McEwen & Seeman, 2006). If the stress is ongoing or chronic than the “wear

and tear” on the body will result in illness (McEwen, 2003 & 2006 McEwen &

Seeman, 2006). Cortisol is the primary HPA hormone and it can be measured

Send us your draft and goals—our editors enhance clarity, fix errors, and keep your style. You’ll get a pro-level paper fast.

non-invasively and reliably in saliva (Helhammer, Wust, & Kudielka 2009;

Turner-Cobb, 2005; Granger & Kivlighan, 2003). When the body is stressed, the

HPA axis releases higher levels of cortisol resulting in metabolic imbalances

involving blood sugar and insulin, higher blood pressure, faster heart rate, mood

changes, thyroid imbalances and weakened immunological responses (Bruyere, 2009).

Yep! We’ll suggest ideas tailored to your field—engaging and manageable. Pick one, and we’ll build it into a killer paper.

A normal salivary cortisol stress reactivity response consists of a peak elevation

of salivary cortisol concentrations 10 minutes after the cessation of the test stressor

with a decrease to pre-stress levels approximately 90 minutes after the start of the test

(Kirschbaum, Pirke & Hellhammer, 1993). In addition, heart rates peak during the

protocol’s stressful task and then drops to baseline once the stressor stops (Kirschaum,

Pirke, & Hellhammer, 1993). In a recent study, prematurely born age 6 -10 years olds

were found to have an exaggerated cortisol response when faced with a social stressor

Yes! Need a quick fix? Our editors can polish your paper in hours—perfect for tight deadlines and top grades.

in a reliable laboratory paradigm, and more emotional and memory problems

(Quesada, Tristao, Pratesi & Wolf, 2014). Biological stress responses (i.e. cortisol)

play a reciprocating role whether the stress is physical or psychological.

Psychological stress (i.e. social evaluation and the perception of uncontrollability in

the situation) activates the cortisol response (HPA Axis), which in turn effects the

physical systems. Conversely physical stress activation (i.e. pain) of the cortisol

Sure! We’ll sketch an outline for your approval first, ensuring the paper’s direction is spot-on before we write.

system (HPA Axis) is associated with psychological changes in affective and

cognitive processes (Smith & Vale, 2006; Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004).

This study uses a standardized, widely used and well-researched laboratory test

for inducing moderate psychobiological stress responses called the Trier Social Stress

Test (TSST), (Kudielka, Hellhammer & Kirschaum, 2010; Kirschbaum, Pirke,

Hellhammer, 1993). In a meta-analysis of 208 laboratory stress studies, the TSST

was found to repeatedly induce changes in the concentration levels of cortisol (both

serum and saliva), as well as other major HPA Axis endocrines, and to significantly

Definitely! Our writers can include data analysis or visuals—charts, graphs—making your paper sharp and evidence-rich.

cause an increase in heart rate (Kirschaum, 2010; Kudielka, Hellhammer &

Kirschaum, 2010). Two key components of the TSST’s protocol are well studied and

known to be needed to induce a reliable and strong activation of the HPA Axis

measured in salivary cortisol. The components are the psychological stress of the

threat of social evaluation, and the perception of uncontrollability in the situation

(Kirschbaum, 2010; Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004). Over fifteen years of TSST

research has shown an increase by 50-300% over baseline in endocrine,

immunological and cardiovascular parameters (Kirschbaum, 2010).

Young adults born early with immature body systems may not just simply grow

out of it and catch up to those born full term (URI, 2011). Subtle, minor and clear

We’ve got it—each section delivered on time, cohesive and high-quality. We’ll manage the whole journey for you.

differences in attention, hyperactivity, and emotional and socialization effectiveness

have been found during childhood and adolescence (Healy, 2010). Guided by the

DOHaD theory, the developmental challenges of independent living at age 23 years

call for greater knowledge about how mechanisms of stress and capacity for response

are seen in former premature infants. There is minimal research on 23-year-old

Yes! UK, US, or Aussie standards—we’ll tailor your paper to fit your school’s norms perfectly.

outcomes of stress, coping, emotional intelligence, emotional health, stress reactivity

responses and the progression of emotional disorders. More knowledge about the

relationship of premature birth, the neuroendocrine stress response, self-reported

stress, coping and emotional intelligence will expand our understanding of the well

being of young adults and their attainment of developmental milestones. (Mannisto, et

If your assignment needs a writer with some niche know-how, we call it complex. For these, we tap into our pool of narrow-field specialists, who charge a bit more than our standard writers. That means we might add up to 20% to your original order price. Subjects like finance, architecture, engineering, IT, chemistry, physics, and a few others fall into this bucket—you’ll see a little note about it under the discipline field when you’re filling out the form. If you pick “Other” as your discipline, our support team will take a look too. If they think it’s tricky, that same 20% bump might apply. We’ll keep you in the loop either way!

al., 2015; Simpson, 2009; Tarasuik, et al., 2009).

Purpose

The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) framework provides

the theoretical perspective for the proposed study. DOHaD asserts that early prenatal

Our writers come from all corners of the globe, and we’re picky about who we bring on board. They’ve passed tough tests in English and their subject areas, and we’ve checked their IDs to confirm they’ve got a master’s or PhD. Plus, we run training sessions on formatting and academic writing to keep their skills sharp. You’ll get to chat with your writer through a handy messenger on your personal order page. We’ll shoot you an email when new messages pop up, but it’s a good idea to swing by your page now and then so you don’t miss anything important from them.

and neonatal stress seen in HPA axis function affects later health and behavior. It

offers a mechanism to enable the understanding of salient young adult developmental

performance abilities. This is a secondary analysis of a well- characterized cohort of

premature infants categorized by neonatal illness into four groups of prematurely born

infants (Appendix A Measurements) and one group of full-term infants (for a total of

5 groups) who were assessed at age 23 years in a research protocol, which included

measures of stress, coping, emotional intelligence, emotional health and

the Trier Social Stress Test. The purpose of the study is to: 1. Compare the effect of

prematurity on stress, coping, emotional intelligence and emotional health at age 23

years. 2. Examine the neuroendocrine functioning of the stress response and

the stress recovery period at age 23 years. 3. Examine emotional health with HPA

Axis stress reactivity responses accommodating for prematurity and gender. The

knowledge gained from this study can help to inform how neonatal stress of

prematurity effects young adult coping, emotional intelligence, physiological

responses, developmental milestones and emotional health at age 23 years in a sample

at risk for HPA dysfunction. The results can help to identify who may be at risk, the

role of the neuroendocrine systems as an underlying mechanism, and suggest clinical

interventions to be taken to avoid risk factors and promote future adult health

outcomes (Rice, 2012; Kirschibaum. 2010; Sullivan, 2008).

Aims and Hypotheses

In a sample of young adults at age 23, former premature infants with a wide

variation in diagnoses of neonatal illnesses and a full term group, the aims of the

study, with related hypotheses are:

Aim 1. Compare the effect of prematurity on stress, coping, emotional

intelligence and emotional health.

Hypothesis 1. Higher self-reported stress scores, higher use of avoidance

coping types, lower emotional intelligence scores and more emotional health

disorders will be found for the adults at age 23 years born prematurely

compared to the term-born adults.

Aim 2. Compare the salivary cortisol response to social stress between premature

and term-born infants using stress paradigm of the Trier Social Stress Test

(TSST).

Hypothesis 2. Adults at age 23 who were born prematurely will have a

prolonged stress recovery period of the TSST.

Aim 3. Examine the relationship between effect of emotional health and on the

stress recovery period of the TSST measured in salivary cortisol.

Hypothesis 3. The stress recovery period for adults at age 23 years with

emotional health problems will be prolonged compared to adults without

emotional health problems when prematurity is controlled.

Summary

This study used a well-characterized, longitudinal sample of preterm and full term

born infants who have been followed from birth in a series of research studies. The

study used neonatal data and self-report of stress, coping and emotional intelligence,

clinical diagnosis of emotional health, and neuroendocrine function during a social

stress paradigm at age 23 years in a secondary analysis. The study is congruent with

the original, larger, study using the same theoretical framework and relevant variables

to examine self-reported stress, coping, emotional intelligence and emotional health

with the primary biomarker of HPA axis system, cortisol. The overall aim of the

study is to examine self-reports of important emerging adult independent function with

neuroendocrine activity in the well-standardized social stress test, the TSST. The

brain areas most affected by stress are the same areas involved in adapting to stress

and coping effectively (Compas, 2006). Researching these integrated

psychobiological processes through multiple analyses will lead to further

understanding of how stress effects young adults emotional development (Compas,

2006). This study has the potential to add relevant knowledge about salient

developmental characteristics, elements and competencies. The following chapter (2)

provides the scientific literature in support of this study. These include the DOHaD

theoretical framework and developmental milestones at age 23 years old of the

emerging adult who was prematurely born. The use of secondary longitudinal data

for analysis will also be addressed.

CHAPTER TWO

Theoretical Background and Related Literature

In this chapter, selected theoretical perspectives for this study are delineated,

specifically the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD),

neuroendocrine function of the HPA Axis, and prematurity. Age appropriate young

adult development at age 23 years will be described in relation to concepts of stress,

coping, emotional intelligence, and emotional health. Prematurity effects compared

to the full term born for 23 year olds will be understood within a disease

developmental theory integrating both biological and psychosocial aspects.

The discussion will begin with a historical review of the DOHaD theory and the

contributions up until present time. Included is a review of the construct development

of emotional intelligence and the relationship of DOHaD to stress, coping and

emotional health.

Theoretical Perspectives

The relatively new Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD)

theory has gained scientific acceptance within the last thirty years (Wandhwa, Buss,

Entringer & Swanson, 2009). DOHaD postulates that fetal and neonatal stressors

affect the neurological and endocrine systems adaptive responses, specifically the

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which is essential for physical and

psychological growth (Barker & Thornburg, 2013; Carpenter, Gawuga, Tyrka, Lee,

Anderson, & Price, 2010; Wandhwa, et al., 2009; McEwen, 2003; Sapolosy, 2001).

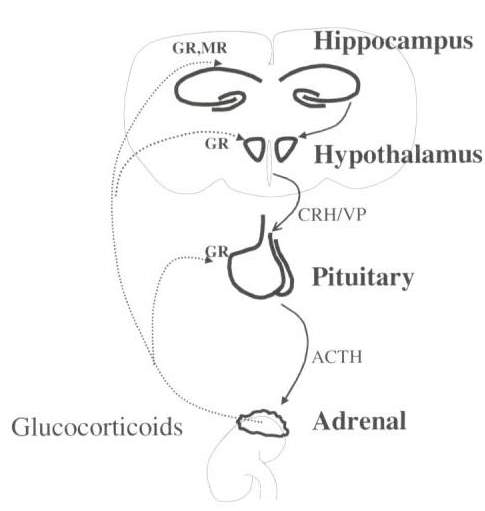

The major stress pathway of the neurological system is the HPA Axis (Figure 1)

which releases cortisol. Cortisol, the most dominant stress hormone that crosses the

blood – brain barrier, has the important function of adapting the body to both physical

and emotional stress responses (Bruyere, 2009). Additionally cortisol is vital in the

regulation of blood vessel tone, the inflammatory response, stimulation of glucose

production, insulin, and metabolism (Bruyere, 2009). HPA functioning is altered by

stress during structural growth periods resulting in permanent programming of early

life stress responses that contribute to disease formation later in life (Sullivan, Hawes,

Winchester & Miller, 2008).

Figure 1

Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis

Figure 1. Reprint by permission from Worth Publishers. “An Introduction to Brain and Behavior (5th Ed.)” by Bryan Kolb and Ian Q. Whishaw, 2016. Copyright 2016 by Worth Publishers. From: AN INTRODUCTION TO BRAIN AND BEHAVIOR 5E, by Bryan Kolb, et al, Copyright 2016 by Worth Publishers. Used by Permission of the publisher.

Premature birth (<37 weeks gestation) occurs at a rate of one out of every nine

births, is the leading cause of infant deaths and long-term neurological disabilities in

children (CDC, 2014). The normal duration of pregnancy is 9 months (280 days)

with full term birth occurring at 40 weeks gestation (Taber’s, 2009). Preterm birth,

either naturally or by cesarean section, is “arbitrarily defined as before 37 weeks”

(WHO, 2015; Johansson & Cnattigius, 2010). Preterm birth can be further

subdivided into: moderately premature (32-<37 weeks), very premature (28-32

weeks), and extremely premature (<28 weeks), (WHO, 2015). The characteristics of

low birth weight and rates of fetal growth has also been used to define prematurity.

In preterm research studies, the combination of gestation weeks and birth weights are

used to avoid any misclassification especially with infants who have growth

restrictions (Johansson & Cnattigius, 2010). Low birth weight is <2500g (5 lbs. & 8

oz.), very low birth weight is <1500g (3 lbs. & 4 oz.), and extremely low birth weight

is <1000g (2 lbs. & 3 oz.), (Johansson & Cnattigius, 2010).

Surviving preterm born infants may have intellectual disabilities, neurological

problems, respiratory, visual, hearing and digestive problems (CDC, 2014; Martin &

Osterman, 2013). Premature infants have experienced prenatal stress, often from

health risk factors in the mother and postnatal stress from months–long intensive

care in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). These early stress experiences

evoke broad biological responses in the underdeveloped premature infant’s

neurophysiological systems including brain growth occurring during uterine

development (Phillips, 2001) and peak growth spurts well into the mid-twenties of

age (Epstein, 1986). Thus, the premature infant’s neuroendocrine system is

frequently activated leading to the inductive development and empirical evidence in

support of DOHaD theory.

Historical Evidence and Perspectives

DOHaD evolved from Barker’s original “Fetal Origins Hypothesis” which

originated inductively from epidemiological studies. (Barker, 1990; 2004, 2007;

Barker & Thornburg, 2013; Wandhwa, et al., 2009; Gluckman & Hanson, 2007;

Reynolds, 2007; Hofman, Regan & Cutfield, 2006). During this time period

multiple retrospective mortality and epidemiological studies from different countries

showed evidence that adult height and geographical differences were related to infant

mortality caused by heart disease (Barker, 1990, Barker, Erickson, Forsen, & Osmond,

2002; Phillips, 2001). An influential study, consisting of 499 people at age 50 born

in England, revealed their current blood pressure measurements and hypertensive risk

factors were strongly related to the measurements of their hospital-recorded placenta

and birth weights (Barker & Osmond, 1986; Barker, 1990). A lack of evidence was

found for the role of some commonly involved environmental variables in heart

disease, such as a high fat diet, and this finding prompted an alternative hypothesis

(Barker, 1995, 2007; Barker & Osmond, 1983). As a result of this landmark study, a

paradigm shift representing a new conceptualization of disease causation occurred

(Barker, 2007). This shift in scientific thinking about adult diseases, which was

defined as degenerative in nature and viewed as a result of gene and environmental

interactions, occurred and resulted in the inclusion of biological programming during

fetal and infant life (Barker, 1990) as a plausible explanation (Gordis, 2009).

Barker’s (1995) initial assumption was: “ fetal under-nutrition in middle to late

gestation, which leads to disproportionate fetal growth, programs later coronary

heart disease (p 171)” lead to further studies from this hypothesis. Later Barker

(2004) refined this to the hypothesis:

“Cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes originate through developmental

plasticity, in response to undernutrition. As it is now known that growth during

infancy and early childhood is also linked to later disease “developmental origins

hypothesis’ is now preferred (p. 114).”

Barker, defined a process of developmental plasticity as: “ a critical period when a

system is plastic and sensitive to the environment, followed by loss of plasticity and a

fixed functional capacity” (Barker, 2007, p 415). According to Barker, developmental

plasticity also has three features: 1. The response will depend on the nature of the

environmental cue. 2. There are critical time periods for different systems when

changes will occur and these changes may be temporary or permanent. 3. Duration of

these critical time periods are different depending on the structure with the brain

periods longer. These changes can be gross, substructure or functional.

The imbalance of fetal nutrients and oxygen was thought to result in an alteration

of not only metabolic yet endocrine functioning leading to smaller birth weights and a

variety of adult pathologies (Drake, Tang, & Nyirenda, 2007; Phillips, 2007; De Boo

& Harding, 2006, Gibson, Carney & Wales, 2006). Despite the scientific acceptance

of this explanation, methodological issues surrounding the use of body measurement,

birth weight or gestation age, and studies designed without a well-characterized cohort

utilizing prenatal and adult health outcomes, as well as observational and prospective

designs, added to concerns about confounding variables (socioeconomic status, diet,

cigarette smoking, physical exercise and selection bias), statistical effect sizes

(attrition and statistical over adjustments) and publication bias (Skogen & Overland,

2012; Erickson, 2006; Godfrey, 2006). A 2003 meta-analysis study addressing

publication bias relating to low birth weight and higher blood pressure found a weaker

association than initially determined yet maintained support for the fetal origins

hypothesis (Skogen & Overland, 2012). Despite a weaker association found, while

addressing some of the common confounding variables as alternative explanations,

better research methodologies resulted and improved the replication of findings

(Gordis, 2009).

Further studies from a variety of countries designed to control for confounding

variables supported the association between low birth weights as a fetal antecedent to

diseases (Barker & Bagby, 2005; Vohr, Wright, Dusick, Mele, Verter, Steichen,

Simon, Wilson, Broyles, Bauer, Delaney-Black, Yolton, Fleisher, Papile & Kaplan,

2000). At the same time debates occurred focusing on the idea that the only

important applicable time period for DOHaD was during pregnancy and the theory

was useful in explaining only cardiovascular diseases (Gluckman & Hanson, 2006;

Godfrey, 2006). Indeed, DOHaD flourished in explaining cardiovascular risk (Bryan

& Hindmarsh, 2006). Later, researchers significantly correlated low birth weight with

increased risk in a number of diseases that are part of the metabolic syndrome

(Hofman, Regan & Cutfield, 2006) such as truncal (middle body) obesity,

hypercholesterolemia, atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease, insulin resistant

diabetes mellitus, cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure, autoimmune disease,

anxiety, depression, chronic pain and headache (Fricchione, 2015). Replicable cross

sectional studies of relationships between disease formations with metabolic illnesses

supported further study of the HPA axis associations.

The results from a retrospective longitudinal study of Helsinki, Finland male

adults, gave credence to the findings that smaller infants have a higher rate of

cardiovascular disease for men in adulthood (Ericksson, Forsen, Tuomilehto, Osmond

& Barker, 2001, Godfrey, 2006). The sample size consisted of 4,630 men born in

Helsinki (1934-44) and utilized child welfare clinic medical health records with

multiple time points of childhood through adult weight recordings, height

measurements and hospital admissions for coronary heart disease (Ericksson, et al.,

2001). Overall, low birth weight was associated with heart disease, low weight gain

was associated with an increased risk of heart disease and rapid weight gain after age 6

was associated with further risk (Ericksson, et al., 2001). As a result of this study,

determining what changes occurred in prenatal growth and those that occurred later

lead to focusing on the interactions of both prenatal and postnatal environments in the

development of adulthood cardiovascular diseases (Ericksson, 2006; Godfrey, 2006).

Concurrently animal researchers showed that exposure of rats during pregnancy

and after birthing, along with their offspring, to a variety of stressors resulted in

elevated stress-induced cortisol levels in the off-spring and disease development

(Phillips, 2001). This study added a “dose-response” relationship, or intensity and

timing of the exposure of stressors to the DOHaD research literature. Animal studies,

pinpointed the HPA Axis response to stressors introduced during critical times of rat

brain growth, that occurred after birth and produced permanent changes in the animals

HPA Axis response (Matthew, 2002; Phillips, 2001). As mentioned earlier, in

humans, critical brain growth occurs during uterine development (Phillips, 2001) and

continues with peak growth spurts well into the mid-twenties of age (Epstein, 1986).

Sterling and Eyer in 1988 coined the word “allostasis” (Sterling & Schulkin,

2004) based on research with monkeys while studying high blood pressure. Allostasis

was now a new paradigm to explain arousal pathology and replaced homeostasis

conceptually. Allostasis involves regulation by: varying parameters and variations in

anticipated demands. A new core assumption now was that physiology is sensitive to

social relations. Allostasis also depended on higher-level brain functioning, other

then basic physiological automatic responses, and involved prefrontal cortex

regulation. Anticipatory regulation for anxiety and satisfaction was found to rely on

the prefrontal cortex through neuronal mechanisms.

McEwen, in 1989, further developed these principles through “allostatic load” and

is credited with the advancement of the theory by publishing research findings related

to human autonomic, central nervous system, endocrine and immune system activity

(Sterling & Schulkin, 2004). McEwen (2006) implicated stress to an event as an

individual biological response factor in the development of a disease. In addition to

acute stress events, McEwen defined the effects of general “wear and tear” (p 367) on

the body as allostatic load that targets the HPA Axis, releasing an end product of

cortisol and can lead to the development of adulthood diseases (McEwen, 2003 &

2006).

The main hypothesis of the DOHaD theory, involves one sensitive brain area of

prenatal and postnatal development occurring in adulthood disease development by

resetting the glucocorticoid endocrines, which is the Hypothalamic-Pituitary –Adrenal

(HPA) Axis (Sloboda, Newnham, Moss and Challis, 2006). McEwen (2008) further

delineated this dimension of the theory by postulating that stress hormones have a

central effect in health and disease by providing protective, damaging and mediating

effects.

These mediating stress effects can be from a physical, psychological, emotional,

cognitive, intellectual, major life events, environmental or social/caring interactions.

Biologically, individuals can either adapt to acute stress (allostasis) or become

overloaded (allostatic load) with chronic stress resulting in pathophysiological changes

(McEwen & Seeman, 2006). See Figure 2.

Figure 2

Stress Response and Development of Allostatic Load

Figure 2. Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd;

Neuropsychopharmacology, 2000, by B., McEwen, Allostasis and allostatic load: Implications for neuropsychopharmacology, Neuropsychopharmacology, 22, 108-124. Copyright 2000 by Nature Publishing Group.

The brain is viewed as not only the controller of the stress response yet conversely

as the target (Rubinow, 2006). The HPA Axis as programmed is effected by the

totality of lifelong stressors (cumulative risk) and negative effects on the brain and

body (allostasis/allostatic load) leading to the long-term consequences of adulthood

disease (Manzanares, Monseny, Ortega, Montalvo, Franch, Gutierrez-Zotes,

Reynolds, Walker, Vilella & Labad, 2014; McEwen, 2012, Sullivan, et al., 2008). In

other words, the adaptability to a stressor or anxiety rather than the initial reaction will

predict long-term outcomes and allostatic load becomes the unifying concept between

cumulative risk and HPA dysregulation (Manzanares, et al, 2014; McEwen, 2012,

Sullivan, et al., 2008).

McEwen did initially base his theory on the idea of homeostasis, which

conceptually is a bodily system that is stable and unchanging (Dictionary.com, 2015)

and postulated there is an optimal level and ideal set point (McEwen, 2004). This

explanation evolved to include the idea of variation (allo) of levels and set points

achieving a balance in the total system (Dictionary.com, 2015). McEwen points out:

Homeostasis is about adjusting this level while allostasis is about the brain

coordinating body-wide changes to achieve stability through change (McEwen, 1998

& 2004). Thus adaptation in a central concept of the theory. Stressors, according to

McEwen result in experiences that are either acute or chronic. Acute stress is the

“fight or flight” response or those responses resulting from major life events. Chronic

stress is defined as the accumulation of minor and daily stresses.

There are four types of allostatic load (Figure 3): normal, repeated, lack of

adaptation and inadequate (McEwen, 2000 & 2007). Endocrine and metabolic

Figure 3

Four Types of Allostatic Load

“Four types of allostatic load are illustrated. The top panel illustrates the normal allostatic response, in which a response is initiated by a stressor, sustained for an appropriate interval, and then turned off. The remaining panels illustrate four conditions that lead to allostatic load: 1) Repeated “hits” from multiple novel stressors; 2) Lack of adaptation; 3) Prolonged response due to delayed shut down; and 4) inadequate response that leads to compensatory hyperactivity of other mediators, e.g., inadequate secretion of glucocorticoid, resulting in increased levels of cytokines that are normally counter-regulated by glucocorticoids). Figure drawn by Dr. Firdaus Dhabhar, Rockefeller University.”

Figure 3. Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd; Neuropsychopharmacology, 2000, by B., McEwen, Allostasis and allostatic load: Implications for neuropsychopharmacology, Neuropsychopharmacology, 22, 108-124.

Copyright 2000 by Nature Publishing Group.

responses protect the body from allostatic load in the short term through homeostatic

adaptation called allostasis. Chronic stressors or allostatic load, whether physical,

psychological or a combination, result in structural brain changes that effect our

physiological and behavioral responses and lead to the development of adulthood

diseases (Ewen, 2003 & 2006).

The stress experience or the stress response that the individual has to a potential

stressor, is the focal point (McEwen, 1998) and added to “Barker hypothesis” of

prenatal stage development, the future time determinants of adulthood diseases

(Skogen & Overland, 2012). Stress as defined by McEwen is a “state of real or

perceived threat to homeostasis” and stressors are “aversive stimuli” while

“maintaining homeostasis through activation of complex responses involving the

endocrine, nervous and immune system” is the stress response (McEwen, 2006).

Luthar, Cicchetti and Becker, 2000, are clearer in their definition of the stress

response, as a dynamic equilibrium, meaning an ability to sway and not as a fixed or

static state. When a good adjustment is achieved across different domains of the

stress response, in the face of significant adversity, then “resiliency” is achieved

(Luthar, Cicchetti & Becker, 2000; Ficchione, 2015). Thus, the capacity to maintain

allostasis while challenged by mental and physical aversive stimuli to well being,

constitutes resiliency (Ficchione, 2015). One Mind Body Medicine equation

(hypothesis) is formulated as (Ficchione, 2015):

Stress (Allostatic Loading) = Selective Vulnerability: Propensity to physical and

Resiliency Factors mental illness

Ficchione (2015) defines resiliency factors as: “relaxation response, mindfulness;

social support/prosociality; cognitive skills; positive psychology; spirituality;

exercise; nutrition; healthy habits”.

According to McEwen (1998) there are two factors that determine the individuals

stress response: how the situation is perceived and the individuals’ general state of

health (determined by genetics, behavior and lifestyle choice), (See Figure 2).

Matthews (2002) added that the timing and intensity of the aversive event and/or an

intervention also effects HPA axis development and functioning. This focus on later

stress experiences added environmental triggers to critical or sensitive growth time

periods as a second possible causal pathway to disease suggesting the involvement of

more than one critical time period (Skogen & Overlad, 2012). Stressors, occurring

prenatally result in adaptive changes within the HPA-Axis, become permanently

programmed, and impact health during adult life (Reynolds, 2013; Sullivan, Hawes,

Winchester & Miller, 2008; Barker, 2007) while later environmental triggers and

responses add to the allostatic load depending on coordination with sensitive growth

time periods (Skogen & Overland, 2012).

The body’s stress response helps individuals adapt to a problem and marshal the

resources to respond which includes releasing response coordinating hormones. A

unifying and central relationship is if the stress response is activated too frequently or

under utilized then the stress-response itself can be more harmful than the stressor and

this concept is called allostatic load (McEwen, 1998 & 2004). There has been

controversy over the labeling of this phenomenon yet the underlying concept has not

been challenged. McEwen (2004) does identify features of some stress processes that

do not change in order to help and adds those processes that do vary in the context of

life cycles, individual experience and responses to the physical and social environment

(McEwen & Wingfield, 2010). The challenge, according to McEwen, in the

definition is that allostasis adds to homeostasis a focus on how individuals have access

to bodily resources to respond to problems with the environment (McEwen, 2004).

Welberg and Seckl, 2001, found that stress during pregnancy could permanently

alter behavioral and/or physiological reactivity to stressors (Sullivan, et al, 2008).

The authors extensively reviewed available research of epidemiological, animal

biological, human biological, anxiety, cognition, neural mechanisms, under-nutrition,

interactions with postnatal environments and glucocorticoid studies. In terms of HPA

function, the evidence showed:

“Birth weight correlates closely with HPA measures from infancy (206), through

adolescence and young adulthood (207) to old age (208). These data suggest that

low birth weight associates with both increased basal and ACTH-stimulated

cortisol levels (207, 209). Taken as a whole, these findings are compatible with

the hypothesis that fetal overexposure to glucocorticoids whether exogenous DEX

or endogenous cortisol may underlie at least in part the connection between the

prenatal environment and adult stress-related and behavioral disorders (Welberg

& Secki, 2001, p 123).”

As this evidence became available another shift in thinking about adulthood

disease formation occurred and became widely accepted by the scientific community

(Skogen & Overland, 2012; Salonen, Kajantie, Osmond, Forsen, Yliharsila, Paile-

Hyvarinen, Arker & Eriksson, 2011; Gluckman & Hanson, 2006; Godfrey, 2006).

The scientific community was now in consensus that relevant life periods are on a

continuum that includes during pregnancy, infancy and throughout the life span

(Gluckman & Hanson, 2006; Godfrey, 2006). The focus of the theory was now

based on two main assumptions. The first assumption is early life events that occur

during periods of critical biological growth partially determine future adulthood

disease development and secondly, this has implications for both disease development

and promotion of health (Gluckman & Hanson, 2006; Godfrey, 2006). DOHaD

theory research then branched into three major areas of interest: 1. Maternal, fetal and

postnatal nutrition, 2. Preterm birth and, 3. Epigenetics (or gene modification),

(Wadhwa, et al., 2009; Waterland & Michels, 2007).

DOHaD theory has been applied to a variety of diseases and health concerns:

behavioral, cancer, cognitive, diabetes, metabolic, muscular, neurological,

psychological and respiratory (Barker & Thornburg, 2013; Gluckman & Hanson,

2007; Hofman, Regan & Cutfield, 2006; Barker, 2005 & 2004). The theory is widely

used in behavioral medicine and specifically with interventions directed at reducing

stress responses (Benson, 2015). Researchers are also exploring the effects of

stressors, as measured by cortisol levels and magnetic resonance imaging, with major

psychiatric disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorders, anxiety responses, stress

responses, cognitive functioning, eating disorders, childhood disorders, personality,

long-term effects of child abuse, psychosis and addictions (Nosarti, Murray & Hack,

2010). Indeed, anxiety, an autonomic nervous system response triggered by HPA

functioning, is a general symptom of stress and co-occurs with other psychiatric

disorders, especially depressive disorders (APA, 2000).

Theory Analysis

DOHaD a relatively new theory addressing the origins of adulthood disease is

widely accepted, utilized in clinical interventions and research studies. Originating

from epidemiological study results DOHaD has developed into a major disease

causation theory. The original theory was intended to explain one aspect of disease

causality and to be applicable to multiple diseases including those “future entitles yet

unknown” (Barker, 2007). Extending the original Fetal Origins Hypothesis, beyond

the initial hypothesis of environmental influences during pregnancy has an effect on

later development, expanded the perspective beyond biological determinism (Skogen

& Overland, 2013). The addition of stress responses through further refinement of

the HPA Axis dysregulation hypothesis, multiple critical time periods and life span

influences took into consideration the role of other causal issues. In addition to

physical stressors, an individual’s perception of stress as threatening or uncontrollable

has been shown to activate the HPA axis as well as coping styles choices affects on

later life stress-related disease development (Figure 4). The continued development

along this thinking moved DOHaD to a fuller life course perspective with multiple

causal factors including emotional health (individual perceptions of stress interpreted

as threatening or not) environmental (such as parenting) and for some the addition of

the biological bases of mammalian evolutionary attachment (social influences)

perspectives (Skogen & Overland, 2013; Fricchione, 2011).

DOHaD theory defines a plausible biological temporal relationship between

disease formation and the role of the HPA axis. Research results show an association,

of a dose-response relationship of intensity and timing of stressors, and replication of

Figure 4

The Cardiovascular Toll of Stress (Emotional and Physical Stressors, HPA Axis &

Health)

Figure 4. Reproduced with permission of Lancet Publishing Group; Brotman, D.J., Golden, S. H., & Wittstein, I.S. (2007) The cardiovascular toll of stress, The Lancet,

370, 1089a1100.

findings in specificity to stress-related illness, although the majority of research

in the United States, has been at discrete time periods in a person or population’s life.

DOHaD theory states the necessary condition of structural and functional changes

prenatally and whether any of this is irreversible remains to be seen (Skogen &

Overland, 2012). Some common confounding variables as alternative explanations

have been addressed and the national government (National Institute of Health) has

prioritized the use of longitudinal studies to address the complexities of what factors

(NIHR, 2015), may or may not be sufficient or necessary for disorders.

Literature recommendations for further research focus on utilizing regression

modeling statistical strategies to address: the association between the two variables of

early exposure and adult outcomes, intermediate exposures, the interaction between

the early exposure and intermediate variables and to what degree the intermediate

variable is related to disease outcome (Skogen & Overland, 2012). Research into the

effects of stress experiences on HPA Axis development, function and dysregulation

also requires addressing the roles of birth term, gender and social inequalities as

confounding moderating variables (Matthew, 2002; Sapolsky, 2009). The renewed

interest in DOHaD theory is leading researchers into areas of study that promise to

identify risks and protective mechanisms; locate periods of transitions into pathology,

develop preventive and possibly corrective interventions to intervene in the

progression of disease pathologies over the course of a lifetime (McEwen &

Wingfield, 2002; Sullivan, Hawes, Winchester & Miller, 2008; Ben-Sholmo & Kuh,

2002).

Socioeconomic Status (SES)

Many socioeconomic status (SES) factors are associated with low birth weight,

coronary heart disease, under nutrition, low literacy rates and health disparities

(Senterfitt, Long, Shih, & Teutsch 2013; Baber, Muzaffer, Khan, Imdad, 2010).

Social and economic factors are considered the largest single predictor of health

outcomes and influencer of health behaviors (Senterfitt, et al., 2013). Disparities

between countries in preterm birth weights have been partly explained by differences

in SES (Johansson & Cnattigus, 2010). Multiple studies have found that the lower

the social, education, and economic position the higher the unhealthy behaviors (i.e.,

smoking, physical inactivity) and inability to engage in healthy behaviors (Senterfitt,

et al., 2013).

The World Health Organization (WHO, 2015) includes determinants of SES

consisting of: the physical environment, the person’s individual characteristics and

behaviors (including how they “deal with life’s stresses and challenge, (p 1)”, social

support networks, genetics, available health services and gender. Additionally, a

WHO (2003) sponsored study, found middle-class office workers and lower ranking

staff has more disease and die earlier than higher positioned workers. The WHO

report (Wilkinson & Marmot, 2003) focuses on ten main areas of what is known:

1. Life expectancy and shorter life spans occur further down the social ladder.

2. Stressful circumstances lead to worry, anxiety, inability to cope that is damaging to

health. 3. Foundations are laid in childhood: “slow growth and poor emotional

support raise the lifetime risk of poor physical health and reduce physical, cognitive

and emotional function in adulthood, (p 14)”. 4. Poor life quality shortens lives.

5. Stressful workplaces increase the risk of disease. 6. Health risks of

unemployment increases the rates of premature death. 7. Supportive relationships

contribute to health. 8. Individuals addictions to alcohol, drugs and tobacco numb

difficult conditions and lead to downward mobility. 9. Healthy food is a political

issue. 10. People’s dependence on cars has increased resulting in less walking and

social contact and more traffic accidents and air pollution.

One of the earliest criticisms of the interpretations from DOHaD studies is the

the confounder of SES could explain results used to support the theory (James,

Nelson, Ralph, & Leather, 1997; Skogen & Overland, 2012). James, et al, (1997)

found lower socio- economic groups have more premature and low weight births,

more illnesses, more risk factors and less nutritional diets. The DOHaD theory

emphasizes that chronic exposure to stress mediators of the HPA Axis and the

sympathetic nervous system effects multiple organs resulting in disease (Dowd,

Simanek & Alello, 2009) although SES confounding variables in earlier studies were

not adequately controlled or interpreted.

Allostatic load has been used to explain part of the association between SES,

health and disease. Lupien, King, Meaney, & McEwen (2001), as one goal of three,

explored the possibility that because lower SES status involved higher stress and

fewer coping resources then morning salivary cortisol levels would differ from other

SES groups. The cross-sectional experimental design study, utilized 307 children

from a school setting, with 6 age groups (6-16 years old) and two categories (low and

high) of SES. Overall findings showed that lower SES in children related to higher

cortisol levels with the impact of SES on cortisol absent after transition to high school.

The authors identified four possible social explanatory factors of: changing status,

influence of peers, influence of youth culture, and resilience.

In contrast a systematic review of the literature, extending up until June of 2009,

on SES and biomarkers of physiological systems, was conducted by Dowd, et al.,

(2009) to address SES, cortisol levels and indirect measures of allostatic load. A total

of 26 studies met the inclusion criteria of reported associations between an indicator of

SES and cortisol, and/or allostatic load. Fourteen of these studies utilized salivary

cortisol secretions. The findings overall were mixed with little evidence that lower

cortisol related to lower SES and lower SES related to higher allostatic load

measurements. Overall, the authors found more studies with no associations of

cortisol to SES than the intuitive finding of lower SES associated with higher cortisol

levels. The unexpected findings were attributed to differences in the nature of this

relationship or inconstancies in measurements and analysis of both cortisol and SES.

Standardization of cortisol procedures and analysis, variations in SES indicators used,

and the exclusion of subjects using stimulators of cortisol such as smoking, were

major recommendations for future research. Although the review focused on cortisol

level daily patterns and indirect measurements of allostatic load, both laboratory stress

induced and dexamethasone challenges, were felt to provide more controls for

research on the differences of SES on HPA function.

Pluobidis, Benova, Grundy & Layton, 2014, identified four major hypotheses

from the literature about the associations between SES and later life health: 1. Early

life SES directly effects later life health. 2. Early life SES indirectly effects later life

SES. 3. Early life and later life SES effects health through accumulation of risk.

4. Early life health indirectly effects later life health via later life SES. A sample of

aged 50-53 years was taken from an English longitudinal study on aging. Multiple

measurements of early life and later life SES, health, and fibrinogen levels (indicator

of aging) were obtained. The four major hypotheses were compared through

statistical modeling. In general, results found early life SES extends directly until the

beginning of old age and predicts health at age 65 and older yet fibrinogen levels will

vary.

Co-existing with SES are social risk factors defined as (Msall, Sullivan & Park,

2010): “suboptimal home and community environment, poverty, domestic violence,

drug addictions, crime, hunger, and poor quality housing (p 224).” The conditions

of low SES along with access to care issues, coping with multiple adversities,

helplessness and low self-esteem; contribute to the risk of preterm births (p 225)

along with ethnicity, family history, maternal characteristics, multiple pregnancies and

air pollution (Johansson & Cnattigius, 2010; Msall, Sullivan & Park, 2010).

Low SES is consistently associated with poor health and disease yet how this gets

translated into biological risk is uncertain and studies have shown inconsistent and at

time weak results (Pluobidis, Benova, Grundy & Layton, 2014; Senterfitt, Long, Shih,

& Teutsch 2013; Baber, Muzaffer, Khan, Imdad, 2010; Dowd, Simanek & Alello,

2009; Wilkinson & Marmot, 2003; Lupien, King, Meaney, & McEwen, 2001).

Methodological issues in past studies have helped confound the influence of SES and

effected some interpretations of DOHaD theory evidence.

In this study, participants’ selection criteria at birth, as designed in the original

research, involved representation from all SES groups in each variable of birth

status (preterm and full-term born) to control for this effect. Additionally later SES

status at age 23 was assessed for possible individual differences and SES group

variations from the prenatal time period. Multiple measures of SES status, in addition

to income, were used and included standardized instruments, education level,

occupation level categorization and neighborhood ratings (Farrington, 1991).

Race and Ethnicity

The Center for Disease Control (CDC) found differences in preterm birth by race

and ethnicity and statistically analyzed the relevant differences, using percentages, and

z tests at the 95% confidence level (Martin & Osterman, 2013). The percentage

results were: 1. Black infant preterm birth rate (17.1%) was 60% higher than for

White infants (10.8%). American Indian/Alaska Native (13.6%) and Hispanic

(11.8%) preterm birth rates were higher than White infants. 2. Black infants had

double the early preterm birth rate (6.1%) than Whites, 25% higher than Hispanics

(Reagan & Salsberry, 2005), and other ethnicities (2.9%). 3. Black infants were

40% “more likely to be born late preterm than White infants with Hispanic infants

more often than White infants, (Martins & Osterman, 2013).”

Reagen and Salsberry (2005) studied the health disparities of preterm births

among Blacks, Hispanics, and Whites focusing on social contexts of neighborhood

disadvantage and cumulative exposure to income inequality while controlling for

individual risk factors. Neighborhood poverty and housing vacancy rates increased

the rates of premature births for Blacks while income inequality directly effected only

Hispanics (Reagan & Salsberry, 2005). Not withstanding these findings, the close

relationship of social risk factors from low SES to ethnicity (Msall, Sullivan & Park,

2010) confounds the separation of SES from ethnicity effects. Likewise, other

epidemiological studies have shown, that among the multiple causes for spontaneous

preterm births, being a member of the Black race, is also a risk factor (Goldberg,

Culhane, Iams & Romero, 2008).

Mustillo, Krieger, Gunderson, et al., 2004, found self-reported experiences of

racial discrimination by Black women were related to premature birth weights and

may contribute to disparities in perinatal health between races (Black 50%: White

5%). One landmark study accounting for social disparities, showed that even college

educated Black women have an increase rate of premature births when compared to

White college educated women (Schoendorf, Hogue, Klieinman, et al., 1992). In past

racial and ethnic disparities research, studies have separated their focus on either the

social construct of race or the biological processes (Kramer & Hogue, 2009).

A systematic review of the research literature, in 2009, focused on integrating the

racial biological and social patterning of premature births, with the expressed purpose

of ‘understanding the etiology of black-white racial disparities in preterm birth

(Kramer & Hogue, 2009, p 85)”. Over 1,459 citations were reviewed spanning from

1960-2009. Studies utilizing ultrasound-based measurements and data cleaning

methodology approaches that decreased misclassification were utilized. Conceptual

framework reviews lead to 3 primary biological pathways mediating the racial

disparities in preterm birth: placental dysfunction, HPA dysfunction and

maternal-fetalinflammation. Pre and peri-conceptual maternal health as well as

genetic and epigenic pathways studies were included in the review. Overall the

researchers found evidence to support socially patterned maternal stress as a cause of

racial disparities. The identification of few studies addressing genetics and the

challenges of controlling for multiple causal explanations prompted the authors’

suggestions for future research. The suggestions included incorporating biological

markers into socially focused preterm birth studies as well as improved

epidemiological design studies.

In this secondary analysis longitudinal study, the original racial and ethnic

composition of the sampling is predominately White and reflective of the population

and geographical location in Southeastern New England from 1985 to 1989 (Sullivan,

et al., 2008). The homogenous composition of this study population will be

applicable to the White racial group and not reflect the disparities inherent between

Black and Hispanic populations. The identification of the White racial group preterm

health outcomes from 1985-1989 may contribute to further knowledge of health

advances made since that time period and could possibly be utilized to compare the

associated magnitude of racial disparities today.

Gender

Globally, males are slightly more likely to be born prematurely than females

(Katz, Lee, Kozuki, et al, 2013). Decades of past research have shown males born

prematurely have higher mortality and morbidity and the phenomena is often referred

to as “male disadvantage” (Brothwood, Wolke, Gamsu, Benson & Cooper, 1986;

Stevenson, Verter, Fanaroff, et al., 2000; Banga, Barche, Singh, Sheehan &

Vasylyeva, 2015). The confirmed risks of high blood pressure and placenta

abnormalities to the pregnant mother carrying a male fetus is thought to occur

secondary to sex differentiation hormones in utero and at conception (Katz, Lee,

Kozuki, et al., 2013, Ingemarsson, 2003). Moreover, Sweden national figures show

death rates are higher for males by 55- 60% when born between 23 and 32 gestational

weeks (Ingemarsson, 2003). Immediate complications of respiratory distress

syndrome are greater for prematurely born males and cognitive recovery after

intracranial hemorrhage is less when compared to premature females (Imaemarsson,

2003). Similarly, in the United States, males are also more likely than females

(OR = 1.21; 95% CI: 1.02 – 1.42) to be born at 33 to 36 weeks (McGregor, Leff,

Orleans & Baron, 1992). To put it another way, if a male and female are born at

the same prematurely gestational age then male infants risk becoming more seriously

ill than females (SMFM, 2015).

While prematurity survival rates have increased, the prematurely born at 25 weeks

will develop disabilities (1:10) such as lung disease, cerebral palsy, blindness or

deafness; 50% disabilities; and more commonly cognitive and neurological

impairments (Banga, Barche, Singh, Sheehan & Vasylyeva, 2015). A retrospective

chart review of 160 (male 59% and female 41%) pediatric records at a Texas clinic

focused on children and adolescents born prematurely and any gender differences in

medical diagnoses. The sample consisted primarily of White (39.2%) and Hispanic

(38.0%) races born prematurely and between 10 and 21 years old at the time of the

chart review. Gestational ages were divided into two groups of 32-37 weeks and

< 32 weeks with birth weight divided into 7 groupings ranging from extremely low

birth weight to large for gestational age. The incidence of neonatal complications

between genders was assessed according to: jaundice, metabolic complications,

respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis, intracranial hemorrhage and hypertension.

Long-term morbidities included ICD-9 diagnoses of: asthma, allergic rhinitis, cardiac

defects, behavioral issues, developmental delays, growth delay and kidney anomaly

and diseases. Even though, more preterm born males were at weights appropriate for

their gestational age, the study found males had a higher incidence of neonate

complications especially: jaundice (63.1 vs. 36.8%; p = 0.02), metabolic issues

(64.2% vs. 35.7%, p = 0 .03), and respiratory distress syndrome (60.5% vs. 39.4%,

p = 0.02), (Banga, Barche, Singh, et al., 2015). In contrast, prematurely born

females weights were primarily small for gestational age. No differentiation between

genders for neonatal diagnoses of intracranial hemorrhage, sepsis or hypertension

were identified. The only significant gender difference in long-term morbidities

found was notably in behavioral issues for males and mostly diagnosed with attention

deficit hyperactivity disorder (6% vs. 2%; p < 0.01), (Banga, Barche, Singh, et al.,

2015).

The prematurely born female chances of survival are higher than males yet Black

prematurely born females, weighing about 2.2 pounds or less, have a higher rate of

survival than their White peers (UF, 2006). Researchers (UF, 2006) who studied

vital statistics from Florida, between the years of 1996 and 2000 utilizing records of

5,076 babies born in the state, found females at lower birth rates faired better with

Black females fairing better overall. Although the researchers are yet unable to

explain why this racial and gender phenomena exists it is known that female

premature babies in general have more developed lungs than males (UF, 2006).

Finally, there are a few decades of history of the vulnerability of preterm males

over preterm females for increased mortality and morbidity. Studies have shown

despite advancements in preterm neonate care this phenomenon continues to exist as a

risk to full term pregnancy and neonatal complications with male births. A few

endocrine and biological adaptation explanations have been proposed without any

known etiology of this gender-related health disparity (Banga, Barche, Singh, et al.,

2015). In this study, overall gender differences as well as gender and birth status

interaction are analyzed to identify the direction and strength of this effect (Baron

& Kenny, 1986).

Prematurity and Development at Age 23 as Emerging Adults

Multiple factors including SES, race, gender, environment and lifestyles, to

mention a few, influence the health and the formation of physical diseases and

emotional health in all adults. The prematurely born Age 23 emerging adult

entered this world with the disadvantage of multiple immature bodily systems.

Additionally, as has been previously stated, human brain growth occurs during uterine

development (Phillips, 2007), the newborn’s central nervous system (CNS) evolves

rapidly and peak growth spurts continue well into the mid-twenties of age (Epstein,

1986) resulting in multiple sensitive time periods of critical influence. In preterm

infants who require extensive neonatal intensive care, it is possible that the HPA Axis

is repeatedly activated which may result in permanent programming of early life

responses (Maniam, Antoniadis, & Morris, 2014; Reynolds, 2013; Sullivan, Hawes,

Winchester & Miller, 2008). Routine medical procedures activate the newborns

stress response system to react and moderate levels of endocrine hormones have been

found (Jensen, Beijers, Riksen-Walravan & de Weerth, 2010) that contributes to

alterations within the HPA Axis or fetal programing from cell death, and failed or

delayed responses of the central nervous system (CNS), (Sullivan, Hawes, Winchester

& Miller, 2008). See Figure 5

Figure 5

Prematurity, Postnatal Stress and HPA Function

Figure 5. Reprinted by permission Mary. C. Sullivan. 2008-2013. In “Risk and

protection in trajectories of preterm infants: Birth to adulthood (Grant # NIH R01

NR003695-14).” Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of

Nursing Research.

Structural differences in the brains of premature low birth weight infants with

alterations continuing into adulthood have been found by researchers (Nostarti,

Murray & Hack, 2012). Measurements of brain pathology using a variety of

biomarkers, such as salivary cortisol levels as an endocrine marker of the HPA Axis

activation is in wide use and may serve as a transitional marker for psychological

pathology (Turner-Cobb, 2005).

Feldman, Weller, Sirota & Eidelman (2002) in Israel, studied the effects of

mother to infant (or Kangaroo Care) skin-to-skin contact on both prematurely and

full term born infants. Specifically they examined “infants’ capacity to regulate sleep

and wake states, organize behavior, regulate negative emotions, modulate arousal,

coordinate attention to mother and an object, and sustain effortful exploration of the

environment (p 194)”. The infants born prematurely showed an abnormal response

to stimuli and often could not inhibit reactions. Three theoretical perspectives were

included: There is unique time windows for input required for optimal development

of the central nervous system and behavioral organization. Sensory development is

sequential and lastly maternal proximity organizes sleep, rest and behavior inhibition.

A prematurely born group with intervention (n = 73) and a matched control group

(n = 73) without intervention was used. Pre and post interventions as well as

multiple time point measurements were used. The premature infants who received

skin-to-skin contact from the mother were found to benefit by improved behavior

organization and emotional regulation when they reached full term. Hence, self

regulation and the ability to adjust behaviors to the situation is a challenge to the

preterm infant, requires environmental control and sets up regulation parameters

overtime (M.C. Sullivan, personal communication, November 11, 2014).

Affect regulation of emotional experiences to serve a purpose or goal

contribute to meeting developmental milestones and adult maturation while emotional

influences on decision-making have been found during adolescent to contribute to

behavioral (alcohol and nicotine dependence), emotional and clinical disorders (Dahl,

2001). Prematurely born children are at increased risk for behavioral and emotional

health problems along with associated psychiatric disorders especially anxiety,

depression, inattention and social difficulties (Johnson & Marlow, 2011;

Strang-Karlsson, 2011). Children born at extreme prematurity have been found to

experience a 50-70% higher rate of attention and behavioral problems in school

despite normal IQ scores (Lynn, Cuskelly, O’Callaghan & Gray, 2011). Even

children born near term (34-35 weeks gestation) have a 36% increased risk for

developmental delay or disability at kindergarten age (Rabin, 2009). Preterm born

17-year-old late adolescents have a higher percentage of psychological problems

when compared to the United States national age-related statistics (NIMH, 2007a &

2007b; ADAA, 2007): 11% with ADHD compared to 3-5%; 12.1 % diagnosed with

depression compared to 5%; 9.8% diagnosed with anxiety disorders compared to

3.1% (Sullivan, 2008). Thus, prematurity is associated with behavioral and

emotional health issues, as well as, psychiatric disorders from preschool through

adolescence age, and have risk for continued problems in adulthood.

Miller, Sullivan, Hawes & Marks (2009), reported on their prospective,

longitudinal sample of 186 children, at age 12, grouped into four preterm perinatal

morbidity groups (healthy preterm without medical or neurological illness, medical

preterm with clinical illness but without neurological abnormality, neurological

preterm with severe illness and small for gestational age preterm with or without

medical problems) and healthy full-term comparison group. A variety of biological,

social and physical environmental factors were measured utilizing a battery of tests

and neonatal medical data sources. Differences for neurological status, motor status

and health at age 12 were significant with abnormal high rates in the four preterm

groups compared to the full term group. Total health outcomes of the four preterm

groups were 3.4 times more likely than term births to have overall abnormal health

status at age 12.

A secondary analysis of this data (Wright & Sullivan, 2011) demonstrated that

prematurity measured by birth weight was associated with childhood psychiatric

symptoms at age 12. Additionally, the mother’s perception of their premature child’s

vulnerability and psychiatric symptoms correlated positively at ages 4, 8, and 12.

Sullivan, Msall & Miller, (2012), found a higher percentage than the United

States’ statistics for psychological problems in their age 17 cohort of the study related

to attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD), depression and anxiety. This

prospective study reported on the same cohort at age 17 consisting of 215 infants born

between 1985-1989 with preterm birth weights <1850 grams and grouped by neonatal

morbidity then compared them with a full term group. Outcomes of functioning and

disability included body functions, body structures, activities and participation.

Contextual factors were identified according to the World Health Organization

International Classification of Functioning (The ICF Model, WHO, 2002). At age 17,

180 of the 215 adolescents, completed the standardized assessment process that

analyzed health, neurological, chronic conditions, psychological, environmental-

socioeconomic, personal-neonatal morbidity and gender status. Overall results

indicated that physical long-term effects of prematurity were not only confined to

infants with very low or extremely low birth weight but also included small for

gestational age and preterm infants without neonatal complications. Higher

percentages of psychological problems, 11% ADHD (4.1%), 12.1% (5-8%)

depression, and 9.8% (3.1%) anxiety disorders were found.

Emerging Adults

The age period between 18-25 years old is now termed the period of “emerging

adulthood” due to cultural delays in reaching developmental milestones (Arnett,

2013). In the past, these ages were considered part of young adulthood, when the

taking on of adult roles were not delayed. Emerging adulthood, is now a separate

category in the life span characterized by: identity exploration, instability, self-focus,

feeling in-between adolescence and adulthood and feeling hopeful about future

possibilities (Arnett, 2013). More importantly, emerging adults do not exist in all

cultures and only exist in cultures (middle income) that allow the putting off of adult

roles and responsibilities (Arnett, 2013).

Recent national behavioral trends in transitioning into adulthood have shown

delays in traditional major life events such as age at marriage and parenthood,

instability of residence, higher rates of enrollment in college education and a decline

in emerging adults working for pay (Ingels, Glennie & Lauff, 2012; Arnett, 2013).

Arnett (2000 & 2013) characterizes the self-views of emerging adults, in addition to

not perceiving themselves as an adolescent or an adult, as also not fully accepting

responsibility and not making independent decisions. This may be especially difficult

for those who were born prematurely. In addition during the transition from

adolescence (ages 10-18) into emerging adulthood (ages 18-25) extensive related

endocrine system changes occur and influence bodily processes (Arnett, 2013). This

turbulence in endocrine hormones, involving all brain structures, adds to the life

experiences influencing brain growth and emotional health. An emerging adult born

premature may not have the flexibility or adaptability of the HPA axis responses to

achieve allostasis and resiliency.

Globally emerging adults are experiencing life as less meaningful and health

professionals are increasingly concerned about emerging adults negative behavioral

choices to deal with stress as a way of coping (Hutchinson, Stuart & Pretorius, 2007).

American adolescents and emerging adults have a higher rate of risk behaviors than

other countries (Arnett, 2013). Additionally, emerging adult college students were

more likely than older students to become angry or hostile about negative life events

instead of becoming more anxious and depressed (Jackson & Finney, 2002).

Emerging adults born premature who may have physical difficulties, learning

problems and limitations in social skills have an additional level of coping complexity

during this developmental period (Sullivan, 2008). Considering these challenges at

age 23, it may be expected that prematurely born emerging adults will have difficulty

coping with adult stressors.

During emerging adulthood, exploration and changes occur that often lead to

lasting life choices (Arnett, 2000) with stressors, coping styles and neurophysiological

responses of these life choices effecting overall health (Lovallo, 2005; Somerfield &

McCrae, 2000). Differences in stress exposure, appraisals of stress and coping styles

have been identified in adults with immune system disorders, cardiovascular,

depression disorders, and include a variety of physical and mental diseases (Cohen et

al, 2007; McEwen, Gray & Nasca, 2015; Segerstrom & Miller, 2004). Anxious

adults with comorbid depression have been found to use more emotion oriented

coping than individuals without a comorbid diagnosis (Man, Dugan, & Rector, 2012).

The role of avoidance coping has been associated with the generation of stress that a